On January 25, President Biden issued “The Executive Order on Ensuring the Future Is Made in All of America by All of America’s Workers.”

The basic premise of the executive order is that Federal and Federally-funded contracts should purchase American-made products.

But wait, you might ask, isn’t this already the law?

The answer is a qualified yes, as there are already three laws on the books that mandate federal procurement agents purchase American-made products:

- The first is the Buy American Act of 1933, which was signed by President Hoover on his last day in office.

- The second is the 1982 Buy America Act (a provision of the larger Surface Transportation Assistance Act), which stipulates that purchases for road, rail, or rapid transit projects valued over US$100,000 are American-bought.

- The third is the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, aka “the stimulus package” created in response to the Great Recession, whose funding stipulates all iron, steel, and other manufactured goods purchased must be produced in the United States. (This was later amended to allow Canadian goods, after a row with the Canadian government over NAFTA rules.)

The Devil is in the Details: Interpreting Federal Procurement Regulations

So what difference will the new executive order make?

The answer turns on the ability of the executive branch to interpret the existing laws.

To this end, Biden is establishing a new Made in America office within the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which in turn, will liaise with leaders in each of the Federal departments.

Collectively, they will be tasked with coming up with ways to strengthen the provisions of the Buy American Act of 1933, the 1982 Buy America Act, etc., and issue bi-annual recommendations.

For example, the Buy American Act of 1933 allows for procurement officers to apply for waivers that allow them to bypass the requirement to buy American-made products if, for example, the product is not available domestically, or if it’s 25% more expensive or, rather vaguely, if “doing so is in the public’s interest.”

In announcing his executive order, President Biden said he wants to tighten the waiver process to make it harder for federal agencies to buy foreign goods.

In this order, he is also mandating greater transparency in the procurement process, and specifically, requiring that any waivers, when issued, be published on a publicly accessible website so that American businesses (and citizens) can see where the Federal government is spending money on foreign products.

Transparency is the Most Powerful Trade Tool according to the Author of What if Things Were Made in America Again

It’s this latter point of making the information public that got us thinking about the 2017 book What if Things Were Made in American Again.

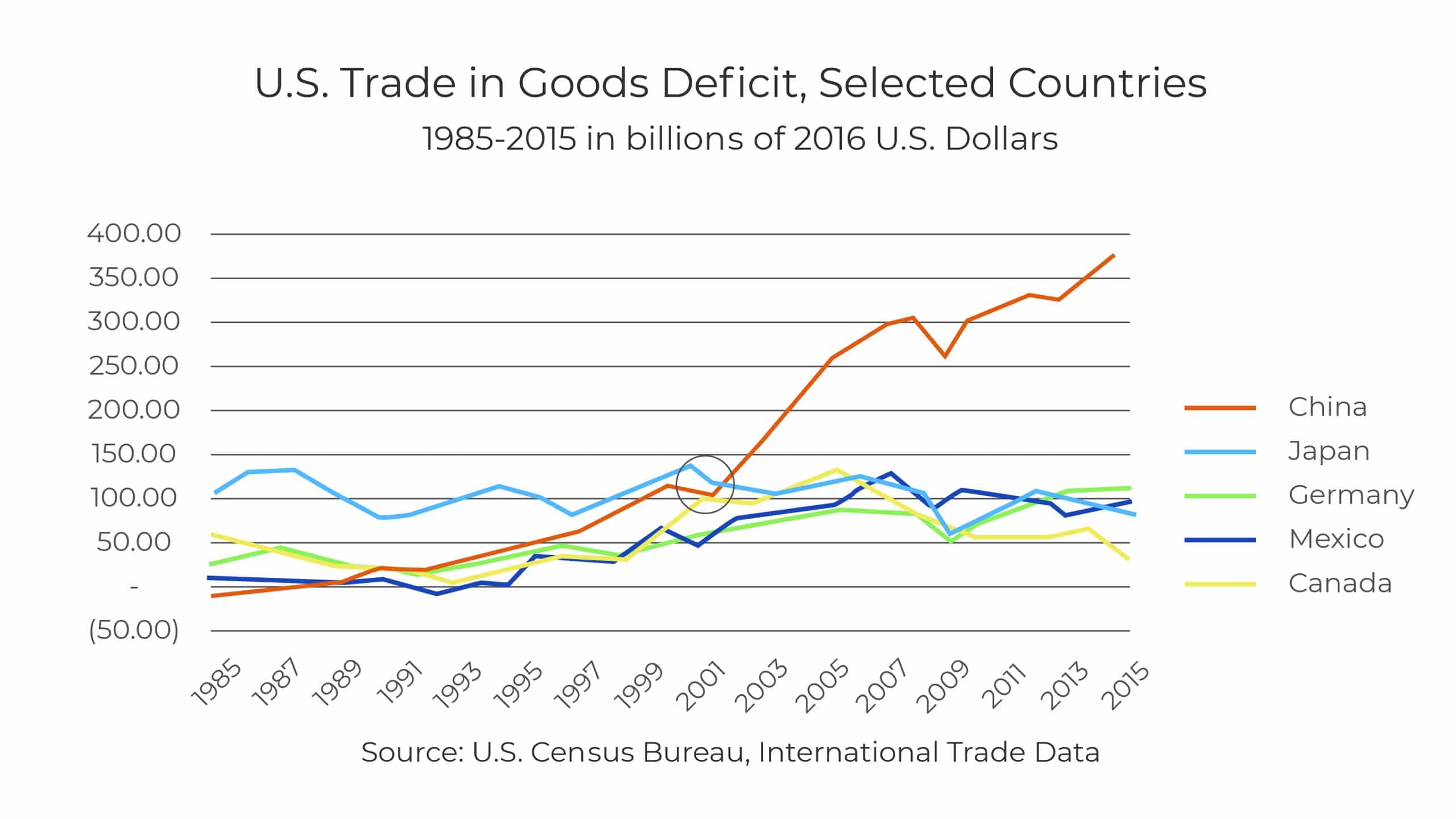

The author, James A. Stuber, outlines the history of US trade from the Revolutionary War days to the present, with a particular emphasis on what Stuber calls the great “hollowing out” of the American manufacturing economy during the 2000s.

Stuber argues that, in the long run, transparency may be a more powerful remedy for trade imbalances than, for example, enforcing trade agreements with the World Trade Organization, where mounting a legal challenge is not only too expensive for most American manufacturing companies – and also too slow to be effective. (Stuber points out new cases can only be mounted AFTER the domestic has suffered damages.)

Stuber’s Seven Reasons Why WTO Challenges are Not Effective in Righting Trade Wrongs

- Relief is not until after harm has already been done.

- It is difficult to know where the harm is coming from.

- It is necessary to provide the foreign manufacturer’s actual cost of production

- It is necessary to define the affected industry and to obtain the participation of 51% of it

- There will be much opposition from importers, retailers, etc.

- The entire process is extremely expensive and time-consuming

- The remedy is never sufficient.

Instead, Stuber says it’s far more effective to promote American-made products to consumers; it’s in our national interest to demand transparency during every step of the sales cycle so that consumers can see the details of American content (including US labor) when making purchasing decisions.

But it’s a lot easier said than done.

Who Determines What is Made-in-America?

Around the world, consumers generally prefer products made locally, a purchasing behavior known as “nationality bias.”

Savvy marketers take advantage of this powerful preference, using “place-based branding” (also known as “made-in image.”) Just think of French Champagne, which is only legally produced in the terroir of the Champagne region of France. Sparkling wine made in California or cava from Spain doesn’t sound nearly as good (or expensive).

Trade negotiators know the value of “country of origin labeling” (COOL), and it’s often the sticking point in intense trade negotiations between countries, where complex “rules of origin” formulas can determine if a product is, for example, “Made in America” or not.

Here in the US, the primary oversight of the COOL rules happens to be divided between multiple agencies (a confusing practice that, in our view, the new Biden “Made in America” department would be well advised to reconsider…).

Broadly speaking, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency is responsible for the labeling of foreign imports, overseeing the ubiquitous labels Made in Germany, Made in China, etc.

On the other hand, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has oversight over Made in America labeling for some categories of domestic products, as well as adjudicating misleading marketing and advertising claims about where products are manufactured.

But as we’ll see in a moment, sometimes other agencies have oversight over what is “Made in America,” as well as how much content and what types of processes (performed in what order) allow products to earn that designation.

Spoiler Alert: Trade relationships are complicated.

Buying an American Made Car Should Be Easy, Right? But it isn’t.

Keeping with the Made-in-America theme, President Biden said in a recent speech that “the federal government also owns an enormous fleet of vehicles, which we’re going to replace with clean electric vehicles made right here in America made by American workers.”

According to the GSA, the Federal vehicle fleet totals around 645,000 vehicles – and, at present, less than half a percent are electrically powered. Assuming a 10% annual replacement rate, the government could start purchasing around 65,000 new EVs every year.

But can we supply enough American-made EVs built by union labor as the President requests?

Tesla would be an obvious choice; its vehicles are made in the US at their Fremont California factories – and in the future, Tesla trucks will roll off the assembly line in Austin, Texas, south of Formaspace’s factory headquarters.

But these aren’t union factories, so the government may turn to other US manufacturers. However, according to Bloomberg, the most obvious choice, the Chevrolet Bolt, which is union-made, has only 24% American content – most of which comes from South Korea.

Ironically, Japanese-owned Nissan may be best positioned for these government contracts, as its EVs are union-made in its Tennessee and Mississippi plants.

So how difficult is it for ordinary consumers to identify an American-made car?

Cars.com did an in-depth analysis ranking the top 91 cars made in America by US labor contribution and American-made content. The top 10 most American vehicles are listed below.

- Ford Ranger (assembled in Wayne, Mich.)

- Jeep Cherokee (Belvidere, Ill.)

- Tesla Model S (Fremont, Calif.)

- Tesla Model 3 (Fremont, Calif.)

- Honda Odyssey (Lincoln, Ala.)

- Honda Ridgeline (Lincoln, Ala.)

- Honda Passport (Lincoln, Ala.)

- Chevrolet Corvette (Bowling Green, Ky.)

- Tesla Model X (Fremont, Calif.)

- Chevrolet Colorado (Wentzville, Mo.)

Theoretically speaking, it should be easy – since the 1994 model year, the American Automobile Labeling Act has required manufacturers to provide this information – not to the FTC, but the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA)!

But, aside from the confusing proliferation of Federal agencies overseeing what’s made in America, there are two more problems.

The first is that since US manufacturers like GM, Ford, and Stellantis (the name for Dodge, Chrysler, and Fiat’s new parent company) have varying degrees of local and foreign vehicles in production, they choose to keep their cards close to the vest, making consumers dig for the information.

The second problem is the government’s Made-in-America classifications are an “all or nothing” system – which can create deceptive results in the final calculations.

What we need is a more detailed, granular calculation along the lines of nutrition labeling. And given that this information is well known to manufacturers who calculate supply chain contracts using modern ERP systems, it should be available.

Disputes between Agencies over What’s Made in America and What’s Not

We mentioned earlier that CBP has authority over foreign-made designations, while the FTC is responsible for domestic ones.

That’s a bit of an oversimplification.

In reality, the FTC’s authority* over mandating Made-in-America labels only extends to vehicles, textiles, wool products, and furs.

(*To be fair, if a company makes a misleading claim about their products being made in America when they’re not, the FTC is authorized to step in.)

Confused yet?

It gets better.

You might have been concerned when we wrote about the discovery of potential cancer-causing agents found in common pharmaceutical products manufactured overseas.

Most consumers probably don’t realize that a high percentage of the active ingredients in their prescription medications are derived from compounds manufactured overseas, mostly in India or China.

But how can consumers know where their drugs are sourced from?

Unfortunately, you won’t get much useful information from the label.

For years, the Food and Drug Administration and the CBP have been locked in a battle with some foreign pharmaceutical companies over how to classify the country of origin in drug manufacturing.

Should the labeling be guided by where the product’s “substantial transformation” takes place – such as where the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is made— or should it refer to the country where the final “fill and finish” is done?

On Feb 10, 2020, the Federal Circuit court ruled in favor of the latter, in the case Acetris Health, LLC v. United States, which ruled that when it comes to contracts under the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), the final manufacturing location determines “where the drug is made” even if all the ingredients are sourced overseas.

Clearly, that’s not what consumers were looking for.

And there’s more.

Did you know it can be illegal to label some American meat products sold to consumers as Made-in-America?

Here is the backstory.

Per USDA rules, the Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) regulations derived from the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 (and later amended by the 2002 and 2008 Farm Bills and the 2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act) require grocery store and supermarket retailers to label what country foods come from. The list of applicable foods, known as “covered commodities,” includes muscle cuts, ground lamb, chicken, goat, wild and farm-raised fish, and shellfish, perishable agricultural commodities, peanuts, pecans, ginseng, and macadamia nuts.

But in 2009, Canada sued the Federal Government, arguing that under WTO rules, the COOL country of origin labeling rules distorted the trade of livestock between the US and Canada, presumably because American consumers would prefer meat from the USA.

A 2011 ruling was made in favor of Canada, and, with Mexico joining the complaint against the US, was upheld again in 2015 – allowing Canada to impose $781 million in retaliatory tariffs against US imports, with an additional $228 million tariffs by Mexico.

All of which explains why you may not even know if some of the meat products in your local grocery store originated in Canada or Mexico.

Building Consumer Demand for Made-in-America Products

Let’s come back to the second argument made by Stuber in his book What if Things Were Made in America Again.

Despite all the difficulties in establishing clear Federal labeling rules on what is (and what is not) made in America, Stuber argues the power lies in consumer’s hands.

They just need to demand the information to make clear choices.

Indeed, recent research from 2020 shows that American consumers are interested in buying domestic products, even if they cost more.

Why shouldn’t Amazon, Walmart, Target, and other major retailers include detailed information on where products are made, including the sources for the major components and location of the factory?

Armed with the right information, American consumers would make different choices.

One retailer is capitalizing on this. As the name implies, the new Made In America Store chain only carries products made in the USA. Business has been good, allowing them to open up a second location in upstate New York during a time that has been difficult for retail stores. The company also has an active e-commerce website.

Formaspace Furniture is Made-in-America

Are you looking for American-made industrial furniture for your manufacturing facility, laboratory research center, warehousing/distribution center, healthcare setting, government facility, or educational institution?

Turn to Formaspace. All our furniture products are built here in Austin, Texas, at our factory headquarters, using locally sourced materials, including heavy-duty American steel.

Formaspace products are available on the GSA schedule (via contract number GSA #GS-27F-0031V) as well as through the TIPS (The Interlocal Purchasing System) Purchasing Cooperative.

If you can imagine it, we can build it.

Find out more. Contact your Formaspace Design Consultant today.