The pharmaceutical industry is facing a wide range of challenges, including the changing market conditions for so-called blockbuster drugs, increased market penetration by generic drug makers, the risk of carcinogen contamination in common consumer drug prescriptions, potential changes in drug pricing regulations in the run-up to the 2020 election, and even market challenges and opportunities stemming from Britain leaving the European Union.

What’s Disrupting Today’s Blockbuster Drug Development Pipeline?

For the pharmaceutical industry, it’s all about the pipeline.

When things are working on all cylinders, it goes like this: pharma companies spend exorbitant amounts of money on research and development of drug candidates — many are expected to fail during clinical trials.

Pressure mounts on those few drugs in the pipeline that make it through the years-long approval process gauntlet — will they rise to the pantheon of “blockbuster” drugs?

The drug makers certainly hope so. In fact, many pharma execs bet their companies on a series of blockbuster drugs to provide the necessary billions of dollars in ROI earned over the life of their drug patents to recoup all their initial investment (including investments in the failed drug candidates) and to make enough profits to pay for the next round of drugs in the pipeline.

But is the classic era of the blockbuster drug over? Indeed, there’s a concern that the rate of discovery of new blockbuster drugs has slowed down.

What seems to be happening now is that fewer, but more powerful “blockbuster” patent drugs are coming to market, including new miracle drugs offering the hope of life-changing cures for diseases such as liver cancer / Hepatitis C.

However, from a financial standpoint, things are different now. Unlike the famous blockbuster drugs of the past (such as statins drugs for cholesterol, or proton pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux disease), many of today’s new generation of blockbuster drugs often cure chronic diseases outright. (What could be better?) However, this means drug makers have to recoup their investments with one course of a single treatment regimen, rather than over a lifetime of sales for each patient.

Adding to the financial challenges are increased drug development costs and the fact that many pharma giants are spending vast sums on acquisitions to add to their drug portfolios. (As a recent example, Novartis is reported to be offering $9.7 billion to acquire Medicines Co. for its cholesterol-lowering drug.)

More and More Chronic Diseases Can Be Cured, But Who Pays?

Curing a chronic disease is a miracle for patients. But who pays for the development costs of these extraordinary drugs? That’s the billion-dollar question. Here’s a relevant example: what price would you pay to cure a single case of Hepatitis C? The answer may be a $100,000 per patient, a price that some say makes perfect economic sense in light of the costs incurred during the drug development pipeline. But it’s a shock to the consumer and to the insurance payers, many of whom are struggling to pay these one-time costs, even when it offers the potential of a lifetime cure.

Furious negotiations and lobbying efforts are taking place across the nation between drug companies (with expensive, one-time use treatments) and the states to find ways to spread the cost of treatment across a broader spectrum of patients to bring the cost down for each individual.

Meanwhile, politicians in Washington are getting the message that drug prices are too high, and something needs to be done about it. Advocates for lower drug prices have lobbied hard for relief, arguing that Americans pay more than their fair share for drugs compared with consumers in other countries.

(Indeed, some studies indicate that “U.S. consumers account for about 64 to 78 percent of total pharmaceutical profits.” )

Surprisingly (given the rancor of today’s politics), there has been a somewhat bi-partisan bill in Congress: The Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act (PDPRA) of 2019.

The bill caps some Medicare drug prescription prices based on a formula that takes into account the cost that consumers in other countries pay. As expected, opinion is divided: consumer advocates hail the idea of Medicare using its pricing power to get discounts from drug companies, while pharma industry representatives and conservative commentators argue this will have a devastating impact on drug development.

The “Disincentivizing” Impact of Generic Drugs on the Pharma Industry

What does a “disincentivized” drug market look like?

We may only have to look at the generic drug market for the answer.

After drugs go off-patent, profits drop off considerably, as generic drug manufacturers step into the market, often offering medications for sale at prices that are a mere fraction of when the drug was under patent protection.

There is little incentive for innovation, or worse, there may not be enough profit for even the generic producers to continue producing them.

The result? Certain drugs, such as the generic version of Cerebyx (fosphenytoin sodium), have become difficult to obtain at times, as only a few manufacturers are producing the drug. (There are reports that over half of generic drugs are down to only one or two manufacturers.)

The risk of having only one manufacturer is well known, thanks to the EpiPen scandal, when, in 2016, the manufacturer Mylan exercised its market monopoly and jacked up prices for the lifesaving pen.

(In October, Pfizer spun off its off-patent drug division Upjohn into a new company that merged with Mylan.)

Risk of Carcinogenic Contamination in Common Prescription Drugs

Contamination is another challenge facing the pharmaceutical industry in 2019.

In an effort to streamline production and reduce costs, an increasing number of drug manufacturers have been relying on overseas production for ingredients used in drug production. (In fact, Bloomberg reports that 80% or more of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in all US market drugs are made in Chinese or Indian factories).

Some point out there is a regulatory loophole at work here: the overseas manufacture of specialty ingredients destined for drug makers receives less scrutiny than, for example, if the same manufacturers created the final drug compounds destined for consumers.

But suspect ingredients are suspect ingredients, as many brand name and generic drug manufacturers came to discover this year.

For example, Valsartan, a hypertension drug, and Zantac (ranitidine) were found to have high concentrations of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), some of which was traced back to China’s Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceutical Company.

Embarrassingly for the US drug industry and the FDA was how the contamination was uncovered in the first place: the Zantac discovery was made by a small pharmacy company, Valisure, located in New Haven, Connecticut, which happens to run its own drug-testing laboratory.

Will the 2020 Election Cause Drug Pricing Regulations to Change Abruptly?

Anger over high prices and contaminated drugs is fueling the political debate in the run-up to the 2020 US presidential election.

Many of the Democratic candidates for President are advocating some form of “Medicare for All,” either by revamping the current healthcare system into a Single Payer model, by creating a “public option,” e.g. a government-supported system similar to Medicare for younger patients, or allowing older Americans to “buy into” the existing Medicare system designed for those 65 and older.

It’s too early to know for sure if these proposals will catch fire with the US electorate in 2020. However, the pharma industry is reportedly gathering its lobbying forces together to take on the threat of “socialized medicine.”

The US-Style Healthcare Debate Goes World-Wide

The domestic US debate about the future of the healthcare industry and pricing models for prescription drugs has now expanded overseas, particularly in the UK and India.

In the UK, the debate revolves around the Brexit quagmire — how will the UK manage its affairs and trade around the world once (or, as some detractors say, if) it manages to extricate itself from the European Union.

Free trade with the US has become a political flashpoint in the lead up to the December 12, 2019, Parliamentary election day.

British politicians arguing against leaving the EU (known as Remainers) have accused the previous Conservative government of engaging in preliminary trade negotiations with the US that would result in opening up the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), which is available to all citizens, to unfair competition by US healthcare companies, jacked-up drug prices, and other privatization measures that will eventually lead to the demise of the NHS.

The Leavers (e.g. those in favor of leaving the EU) call this “poppycock” and maintain that in a post-Brexit, the NHS will continue to fulfill its mission of providing care for all UK citizens. Time will tell (or maybe not, if this debate never ends).

Meanwhile, Brexit plans have disrupted the European drug market. The EMA (European Medicines Agency), which oversees drug approvals in Europe, has decamped from London to Amsterdam.

Predictions of a so-called “cliff-edge” Brexit (e.g. a sudden change without a transition period glide-slope) have also triggered stockpiling of critical medicines, such as insulin supplies, which might otherwise be delayed due to the red-tape which may (or may not, depending on your political view) cause goods crossing to channel to back up at European and UK ports of entry.

The US healthcare policies have also become a political issue in India as well, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi is negotiating a new free trade agreement with the US. Among the issues at hand are India’s caps on drug prices, which US negotiators want removed. US interests are also lobbying to change India’s drug patent policies to allow the term of drug patents to be extended more easily. (Under the Patents Act of India, a patent extension for a drug cannot be granted for a change that does not demonstrate “therapeutic efficacy,” a limitation designed to limit what Indian regulators consider to be unwarranted “add-on” drug patenting in the US.)

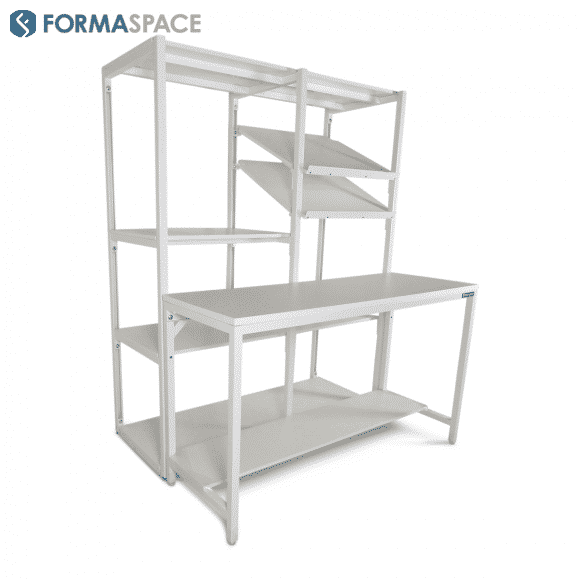

Work with a Leader in Pharmaceutical Laboratory Innovation

When it comes time to update, expanding, or building new pharmaceutical laboratory facilities, we can help.

Formaspace designs and builds custom laboratory furniture for our extensive list of Fortune 50 and Fortune 500 clients here at our Austin, Texas factory headquarters.

If you can imagine it, we can build it.

Take the next step: contact your Formaspace Design Consultant today and find out how we can work together to make your next laboratory project a success.