Malaria is a Mosquito-Borne Disease Dating Back to the Dawn of Agriculture

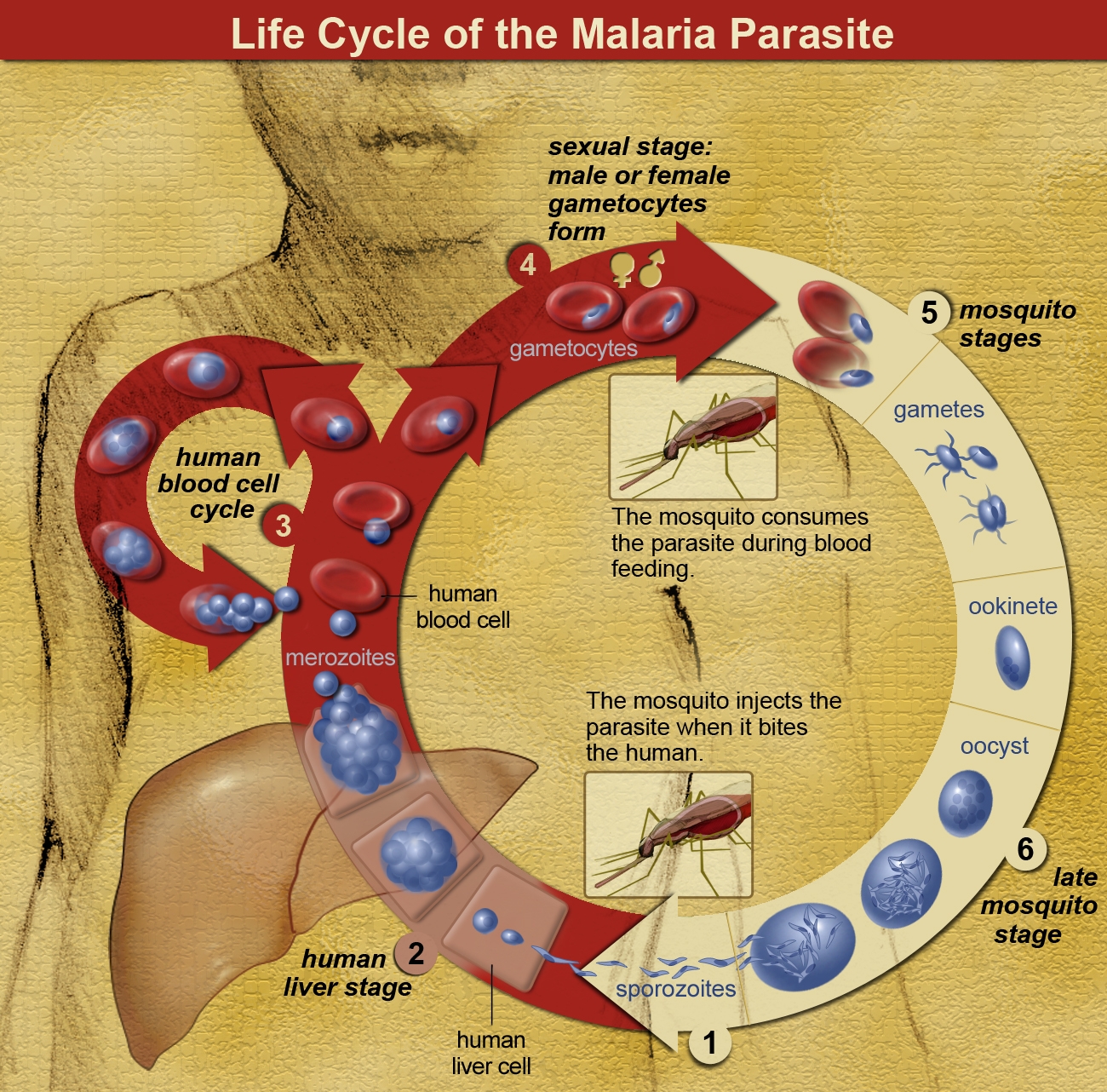

Evidence of malaria disease affecting human populations dates back at least 10,000 years – to the start of organized agriculture. The cause of the disease is a unicellular protozoan parasite (Plasmodium falciparum, among others) that resides in the human liver and spreads to the red blood cells, causing fever, chills, and, if not treated, potentially death. (Those that recover may face a relapse of the disease months or years later.)

Importantly, the parasites cannot create mature offspring in humans; they are completely dependent on a mosquito host taking a bite of human blood to ingest the immature parasite offspring (gametocytes) found in human blood. These mature within the mosquito host, creating infectious sporozoites, which are then passed onto another human via a secondary mosquito bite, where they enter the human liver and begin the cycle anew.

The interaction between humans, mosquitoes, and the malaria parasite was not understood until the mid-1800s. (Previously, the spread was thought to be due to mala aria or ‘bad air,’ hence the name of the disease.)

At first glance, one might assume the complex chain of events required to propagate the disease would offer many opportunities to stop the infection cycle, but malaria has proven to be a wily adversary. For example, multiple parasites in the Plasmodium family can cause the disease, and several different mosquito species can transmit it. Efforts to eradicate one species have often led to a resurgence of malaria transmission by other species.

Malaria parasites have also been able to mutate over time, developing significant resistance to many of the available preventative (prophylactic) and clinical drug therapies.

Weather disasters, such as the massive 2022 floods in Pakistan, have also created discouraging setbacks in national malaria control programs.

Taking Stock of Recent Progress during the 2023 World Malaria Day

Eradicating Malaria worldwide is one of the major initiatives of the World Health Organization (WHO).

During World Malaria Day held this past week, WHO officials recounted the importance of the mission. Eighty-four countries, representing over half of the world’s population, are at risk for Malarial infection, and that figure could grow as mosquito populations increase poleward due to global warming.

In 2021, there were nearly 250 million new cases of malaria and nearly 620,000 deaths – with a disproportionate number of pregnant women, infants, and children under five affected by severe disease.

Aside from the impact on human lives, malaria imposes tremendous downward pressure on the economies of countries where malaria remains endemic, such as Nigeria, which suffers from Africa’s highest Malaria death rate.

The WHO is investing in preventative and clinical therapy research, actively partnering with key NGOs, including PATH / MVI (Malaria Vaccine Initiative), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Gavi / The Vaccine Alliance.

GSK Develops WHO-Approved Malaria Vaccine RTS,S/AS01 (Commercial name Mosquirix) in partnership with PATH’s Malaria Vaccine Initiative (MVI)

The pharma giant GSK began collaborating with the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) in the 1990s to create a vaccine to ward off infection by the most lethal of the malaria parasites, Plasmodium falciparum.

The RTS,S vaccine targets the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) of P. falciparum. To confer protection, the vaccine contains a virus-like protein with 19 N-acetylneuraminic acid phosphatases (NANPs) and a structure known as the “C-terminal” region (composed of amino acids 207-395). This creates a protein structure that mimics the outer CSP surface of P. falciparum, which will stimulate the immune system, priming it to fight off future parasitic infections. The protein then is fused onto a scaffold of HbsAg (the antigen used to make the hepatitis B vaccine) which is cultured in yeast to create the vaccine compound.

The result is RTS,S/AS01, marketed under the commercial name Mosquirix, which targets the most dangerous of the mosquito parasites, Plasmodium falciparum.

GSK partnered with PATH’s Malaria Vaccine Initiative (MVI) to conduct widespread pilot testing campaigns in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi beginning in 2019. Since that time, 4.5 million doses of RTS,S have been administered.

Unfortunately, RTS,S by itself has not demonstrated it can meet WHO’s internal threshold goal of 75% efficacy in preventing malaria. During its initial one-year trial, the efficacy was estimated as high as 55.8% — but over the subsequent four-year trial RTS,S only prevented 39% of regular and 29% of severe cases of malaria. Despite this, there was some encouraging news. Public health researchers determined that RTS,S was more effective when administered in combination with Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), a chemical prophylactic administered during the peak of the mosquito season.

This combination pushed the overall efficacy rate higher, convincing WHO to approve the widespread use of RTS,S in October 2021 to help prevent the spread of Plasmodium falciparum in children.

WHO approves a Pilot Program to Evaluate the R21/Matrix-M Vaccine developed by Oxford University

While WHO celebrated that it finally had an approved Malaria vaccine, the organization remained hopeful that researchers could develop an improved vaccine that meets the WHO threshold goal of 75% efficacy against malaria infection.

Researchers at the Jenner Institute at Oxford University appear to have developed just such a vaccine, called R21/Matrix-M (or R21/MM for short). During a 12-month double-blind trial of 450 children in Burkina Faso, R21/MM demonstrated a 77% efficacy in preventing malaria.

Like the previous RTS,S vaccine, R21/MM uses a truncated version of the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) found on the surface of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum to stimulate a response by the human immune system.

The primary differences between the old and new vaccines lie in the way that the CSP is delivered into the body. As we discussed earlier, the RTS,S relies on a ‘scaffold’ made from the human hepatitis B virus. However, this approach limits the amount of the deliverable CSP component compared to the solution volume required for the scaffold.

In contrast, the Oxford University malaria vaccine design uses a new approach, dubbed R21, to create a higher concentration of CSP particles. The R21 approach does away with the scaffolds by creating vaccine particles expressed directly from a single CSP-hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) within a yeast (Hansenula polymorpha) solution.

As noted, R21 has a higher concentration of active vaccine components compared to the earlier generation RTS,S vaccine – and R21’s efficacy is further enhanced by the incorporation of Matrix-M, a saponin-based vaccine adjuvant produced by Novavax (Uppsala, Sweden). During the initial 12-month trial, the vaccine with a lower dose of Matrix-M component provided 71% protection against initial malaria infections, while the higher dose of Matrix-M offered 80% protection.

These results were confirmed in subsequent trials. In April 2023, Ghana became the first country to award provisional approval of the new R21/Matrix-M vaccine for children between 36 months and five years old, followed quickly by approval by Nigeria. During World Malaria Day, WHO representatives announced that another ten African countries were expected to provide provisional approval in the coming weeks.

Measures have already been taken to produce the new Oxford vaccine in large quantities; according to the manufacturers Novavax and the Serum Institute of India, there will be 20,000,000 doses available for purchase this year.

We are very hopeful that these new malaria vaccines will help stop the spread of the disease in the coming years.

Formaspace is Your Laboratory Partner

If you can imagine it, we can build it, here at our factory headquarters in Austin, Texas.

Take the next step. Talk to your Formaspace Design Consultant today and see how we can work together to make your next laboratory construction project or remodel a complete success.