Location, Location, Location: Many Urban and Waterfront Brownfields are Prime Real Estate Sites with Great Economic Potential

When you are shopping for a new house, it’s not unusual to drive for miles exploring neighborhoods. But developers looking to build large projects often take to the air to scout out large parcels suitable for development. Such was the case with Walt Disney, who took flight over central Florida in 1963 – spying thousands of acres of undeveloped swampland close to new highways south of Orlando.

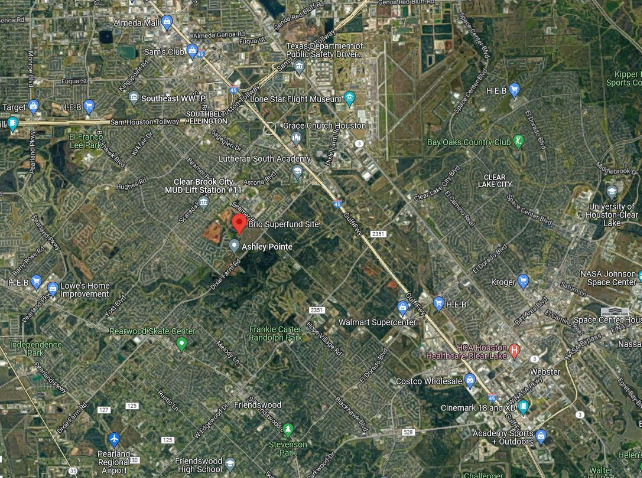

Today, we have the advantage of satellite imagery, which makes site selection much more convenient – however, you may have noticed that some of the most promising vacant real estate parcels – e.g., those near cities or located on navigable waterways – may be vacant for an important reason: they are brownfields contaminated with pollution, unable to be developed without significant remediation.

There is renewed interest in remediating brownfield sites, both from an economic and a health benefits point of view. Due to the way our cities and industries have developed over the last 100-plus years, many of these sites are sitting in prime real estate locations.

Many polluted industrial sites that were once far from city centers when they were built are now considered to be in the heart of metro areas as cities have grown around them. Other industrial sites were built on what are today considered prime waterfront sites – not because they were scenic and desirable but because they offered direct access to water power (such as rivers or dams) or navigable waters and industrial canals used to transport goods by ships or barges.

Depending on the individual circumstances, the presence of brownfields in a community can be a serious, long-term health hazard, a drag on economic development and city planning, or both.

It’s for these reasons (and more) that the Biden administration has promoted and passed new funding to help remediate more contaminated brownfield sites, allowing them to become economic assets for the surrounding communities.

Brownfields, Greenfields, Greyfields, and the Superfund National Priority List (NPL)

Let’s take a moment to review some definitions.

In this article, we are going to focus on brownfields, which are generally defined as having been compromised through past industrial use, generally due to significant pollution or contamination left behind that has penetrated the ground or even entered the water table.

This is in contrast to greyfields, the term urban planners use to describe otherwise uncontaminated sites with structures that could be torn down, redeveloped, or repurposed to create a better economic return (aka a “highest and best use”) – or greenlands, which are virgin vacant lands which have not seen major industrial development in the past and are ready for immediate development.

In the 1970s, two highly publicized cases of industrial pollution, the Love Canal subdivision outside Buffalo, New York, and a field where drums of chemicals had been dumped (known as the “Valley of the Drums”) outside of Louisville, Kentucky, helped galvanize public opinion that something needed to be done to remediate dangerous brownfield sites.

In response, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA) –commonly known as the Superfund law, which documents contaminated brownfield sites and oversees their remediation.

The CERCLA legislation stipulated, where possible, that polluters pay for the remediation; however, in many cases, it has proven difficult to track down “potentially responsible parties” (PRPs) due to poor historical records or the companies responsible having ceased operations or fallen into bankruptcy.

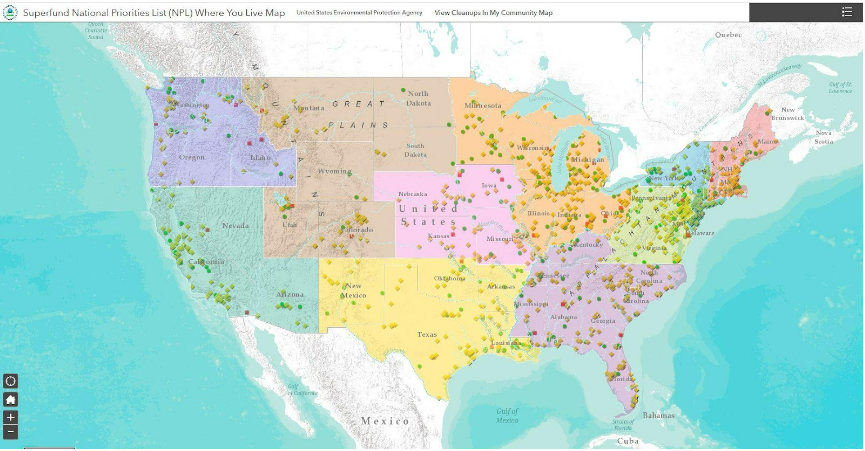

The EPA was put in charge of maintaining a list of Superfund sites (currently around 40,000 nationally) as well as investigating which sites should be remediated first. The EPA’s National Priorities List (NPL) has ranked the worst of 1,333 contaminated sites (see map below for their locations.)

How are the sites prioritized? State agencies and the EPA rely on the Hazard Ranking System (HRS), a zero to 100 scale that quantifies how much of a risk that hazardous chemicals pose at each Superfund site, to identify and rank the worst sites for remediation projects.

The CERCLA law also established the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) to assess the presence and nature of health hazards at specific Superfund sites.

According to the EPA, the most common contaminant found in brownfield sites are:

-

Arsenic

-

Asbestos

-

Lead

-

Petroleum and Hydrocarbons

-

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

-

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)

-

Volatile Organic Compounds

Other less commonly reported contaminants include:

Washington Boosts Funding for Brownfield Reclamation

The EPA works with local communities through its Brownfields and Land Revitalization Program to organize and fund the cleanup and redevelopment of brownfield projects.

As you can imagine, one of the limiting constraints in remediation is finding enough money to fund these expensive remediation projects.

After many years of low funding, there was some good news during the Covid pandemic, and Congress approved the Biden administration’s infrastructure and stimulus plan.

Officially known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, this act set aside more than 1.5 billion dollars to fund projects through the EPA’s Brownfields Program, — the largest budget allocation ever passed for the program.

What are the Steps to Remediate Brownfield Sites?

To understand how a typical brownfield remediation project works, we’ll first take a look at the EPA’s process roadmap for managing a successful brownfield redevelopment, which involves satisfying their requirements for planning, financing, liability insurance, and community involvement. After that, we’ll touch on the actual remediation steps for removing or containing contaminated materials on the site itself.

The EPA’s Anatomy of Brownfields Redevelopment report provides developers with a detailed, step-by-step guide for developers considering taking on a brownfield project in partnership with the EPA and the local, state, or federal government.

Here, the developer must conduct their own due diligence and identify any potential show-stoppers that might preclude moving forward. Once the developer has entered into a ProForma agreement to purchase the property, they need to prepare a redevelopment plan that includes sources of funding (which could include a mix of private and government loans, tax credits, incentives, tax abatements, bonds, subsidies, or grants) as well as purchasing a Pollution Legal Liability (PLL) environmental insurance policy. It’s also important for developers to engage in outreach with stakeholders in the surrounding community to build public support for the project.

The next step is to obtain permits and necessary approvals to proceed with the environmental cleanup operations; we will discuss site remediation activities in the section below.

As the site is being cleaned and prepared for construction, the developer will conduct marketing and pre-leasing to identify potential tenants (if one has not been identified already) and oversee the construction project.

Once the new site is complete, the final steps for the developer are to manage ongoing Operations and Maintenance (O&M) activities, including maintaining any engineering controls, such as asphalt caps or fencing, which restrict access to certain areas of the property that were remediated but not suitable for unrestricted general use.

Now let’s talk about brownfield mitigation methods.

The EPA created Contaminated Site Clean-Up Information (CLU-IN) website as an information hub for members of the waste remediation community. This is a useful place to find informative news and webinars on the latest information on remediation technologies.

According to the EPA, remediation of a brownfield site will involve one or more of the following steps:

· Excavation

Contaminated soil is removed and treated offsite or disposed of in a landfill. New clean soil can be brought in to create a level surface for construction.

The EDGE MC1200 Material Classifier is an example of remediation automation technology at work; it uses a four-stage process to separate aggregates, construction materials, and demolition waste at cleanup sites.

· Tank removal

Many brownfield sites have underground storage tanks and piping systems, which must be removed. The surrounding soil is then tested for contamination and removed if needed.

· Capping

In some cases, it’s necessary to create a barrier between contaminated soil and the surface. This can be done using by adding a geotextile fabric over the surface, followed by a layer of clean soil on top. In other cases, a concrete or asphalt capping layer is used.

· On-site aka “in situ” treatment

In some cases, it’s possible to treat the contaminated soil on-site by injecting chemicals that break down contaminants into less harmful substances, a process known as In-Situ Chemical Oxidation (ISCO). Other variations include injecting gas into the soil to speed up the process or adding chemical binding agents to prevent the contaminants from moving around.

· Bioremediation

This process adds naturally occurring or genetically modified microbes to the soil to convert the organic contaminants to water, gas, or less harmful toxic substances.

· Phytoremediation

Plants that take up contaminants through their roots can be used to remediate brownfield soils. Other plant species can neutralize or stabilize contaminants directly in the soil, or help speed up the process of microbes converting contaminants into less harmful substances.

· Lead and asbestos abatement

Lead and asbestos are inspected and removed by specially-trained licensed contractors. Typically, these materials are removed from the site using specialized equipment.

Brownfield Projects that Showcase the Economic and Community Benefits of Reclamation

One of the success stories for brownfield reclamation in recent years is the Sparrows Point site along the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. Located at the mouth of the Patapsco River that leads into the Port of Baltimore, Sparrow Point was once the home of the world’s largest steel mill. In 2014, Sparrows Point Terminal entered into an agreement with the state of Maryland and the EPA to clean up the site and redevelop it.

Today, the redeveloped brownfield site is home to fulfillment centers of major companies, including Amazon, BMW, FedEx, Floor & Décor, Harley-Davidson, Home Dept, Volkswagen, and Under Armor. These leading companies were drawn to the 3,000-plus acre site, which features a deep-water port, a short line railway, and proximity to Interstates 695 and 95 – putting a third of the US population within a day’s drive.

Another once-heavily industrialized area located on a waterway is Lake Calumet, the largest lake inside Chicago’s city limits. This swampy area on the south side of the city near the border with Indiana was first industrialized in the 1880s, thanks to its connection to Lake Michigan via the Calumet River. A series of industries, including railroad car manufacturing and steel mills, were built here, and the lake later became a dumping ground for steel mill slag as well as a city dump for Chicago’s household and solid industrial waste. The “Lake Calumet Cluster” was designated as a Superfund site by the EPA in 2010. Since that time, the brownfields have been remediated, allowing the creation of Big Marsh Park, the Chicago Park District’s largest reclamation project to date. At the entrance to the park is the new Ford Calumet Environmental Center, a winner of the AIA Chicago’s 2021 Distinguished Building Award. This nearly 10,000 sq ft structure is a resource center for the park, providing facilities for exhibits, classrooms, offices, storage, and a bike repair facility. The industrial look of the building is a nod to Calumet’s past and features weathered steel cladding and exposed nail laminated timber exterior materials.

Future Concerns as Climate Change Puts More Sites at Risk for Contamination

Unfortunately, changes in the climate are making the job of remediating brownfields more difficult.

Rising sea levels and heavier rains are causing historically-contaminated sites to flood, which disturbs sediments and can lead to hazardous chemicals (such as PFAS) dispersing to wider areas, including the water table.

On the other hand, drought is causing a different set of environmental problems.

As lakebeds, such as Utah’s famous Great Salt Lake and California’s Salton Sea, dry up, there are major concerns that the remaining water will become increasingly toxic – and the dried-out lake beds will become a dangerous source of airborne contamination.

The Great Salt Lake has significant amounts of heavy metals in its lakebed, including arsenic, which could become airborne as the lake dries up, putting the 1.2 million residents of the Salt Lake City region at risk.

In southern California, the Salton Sea has been a major environmental concern for years. It was created by accident in the early 1900s due to a breach in an agricultural irrigation canal that flooded the basin with the waters of the Colorado River. During the 1950s, the Salton Sea was promoted as a resort community, offering desert living, fishing, and boating. However, the water continued to retreat rapidly from the shoreline, causing most resort facilities and docks to close. Today, the water has a noticeable stench due to frequent fish kills, as agricultural pesticide runoff drains into the lake, and like the Great Salt Lake, the dried lake bed has become an air pollution hazard as toxic dust gets carried in the wind.

Now, material scientists and mining experts are looking at the potential of reclaiming lithium used in EVs from the brine and lake bed of the Salton Sea.

If this works out, lithium mining could provide an economic solution to solving the Salton Sea’s pollution problems – but if handled incorrectly, it could worsen an already bad environmental situation.

Formaspace is Ready to Help You Tackle Today’s Industrial and Environmental Challenges

If you can imagine it, we can build it, here at our factory headquarters in Austin, Texas.

Whether you are building a new office, research center, laboratory, or environmental remediation facility, we can help.

Talk to your Formaspace Design Consultant today and find out how we can work together to make your next project a success.