We recently had the opportunity to sit down with Flynt Gaines, a veteran Chief Financial Officer in the oil and gas industry to get his input on the market for industrial furniture, as well as his insights on the future developments in the energy market.

The subject of our interview this week is Flynt Gaines, who grew up in Abilene Texas — a city whose economy is dominated by the oil and gas industry. So it’s not surprising that Flynt, who began his career as an accountant, would eventually put his talents to work as Chief Financial Officer (CFO) in the energy market.

It’s because of his background as a finance/business person in the oil and gas industry that we wanted to pick Flynt’s brain — to find out which different operational activities would benefit most from Formaspace’s industrial-strength furniture solutions.

Tell Us about Your Role as an Oil and Gas Finance Executive at Eckard Global, Petromax, and Honcho Energy

Formaspace: First of all, welcome Flynt. Thank you for joining us today. We were quite impressed with your background. Can you share with our readers some of the highlights of your career in the oil and gas industry?

Flynt Gaines: I’m an accountant by training, with a BBA in accounting. I grew up in Abilene, Texas, where cattle, schools, and oil are the primary driving forces of the economy. While in college, I worked for a small refinery company, then I moved to a public accounting firm after I graduated. I went into the Air Force for a while (Flynt still holds his pilot’s license), but at the time, I guess didn’t know then that I’d eventually be spending so much time back in the oil and gas industry.

Formaspace: So what role did you play when you jumped back into the oil and gas industry?

Flynt Gaines: As far as job titles go, Financial Controller is probably an appropriate title for my role at Eckard Global or at Petromax. When I first started, Petromax was considered a small company, doing about a million a year. But we quickly grew it to a substantial size – about $42 million a year – then sold it for $265 million a year later.

Formaspace: Tell us about your role at Honcho Energy. Did you have the same position there as at Echard Global and Petromax?

Flynt Gaines: Well (laughing) the difference was I owned Honcho. I still had the same skills, so I pretty much did the same thing.

After Petromax got big enough that private equity companies started talking to them, they didn’t need the little 1% investors anymore; Petromax had spun off Honcho to handle individual investor relations, which allowed the name brands dealt directly with Petromax.

Later, after Petromax decided that they were going to go their own way, we became a kind of a lease broker working in the Bakken of North Dakota. I think my largest (investment) was 28% in a Continental well. And then we have some smaller percentage investments, e.g. in the range of 2% and 3% in other wells.

Which Market Sectors Would Benefit from Using Formaspace Industrial Furniture?

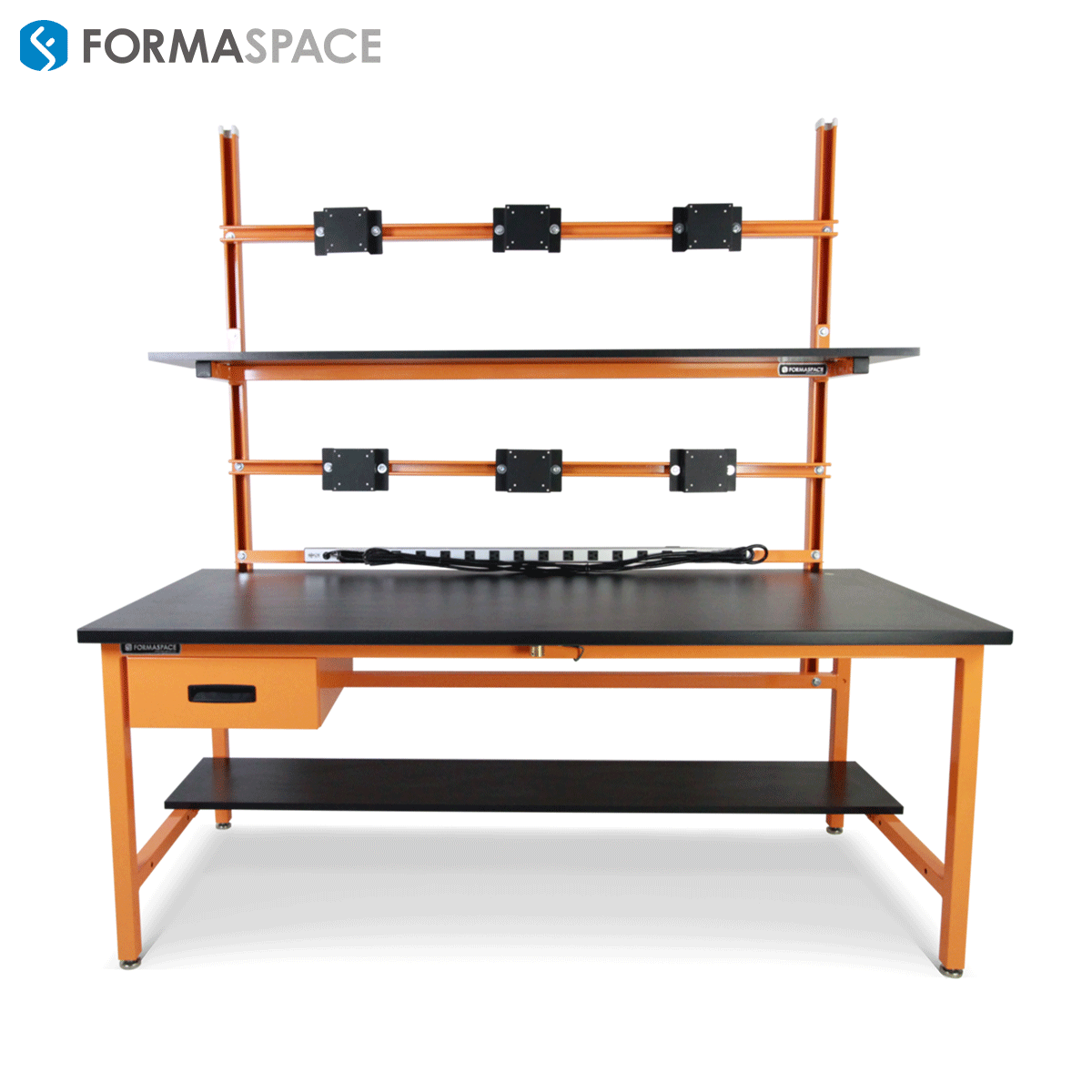

Formaspace: Thank you, Flynt. As you know, we are in the process of validating the market for Formaspace industrial furniture solutions for use in the oil and gas industry. Just little bit of background: From a furniture perspective, we tend to divide the laboratory market into two different sectors: wet labs and tech labs (also known as dry labs). By wet labs, we’re referring to those laboratory facilities that use chemicals and other liquid agents in their day-to-day operations: meaning that the countertops and furniture need to be resistant to chemical exposure. On the other hand, tech labs don’t require as much extensive protection from chemical exposure; these applications range from dry scientific labs to large computer labs.

Flynt Gaines: OK, got it.

Formaspace: So, when we think of the oil and gas companies, we’re working from research done by our national sales manager here at Formaspace who is presently focused on two market sectors: 1) chemical testing laboratories at oil refineries, which would need chemically resistant furniture, and 2) tech laboratories at oil well service companies that are used to support activities, such as down-the-hole drilling.

Could you please comment on this, based on your experience in the industry, so that we might have a better understanding for our readers?

Flynt Gaines: Well, I think that definition is probably very accurate. The oil refineries do have lots of corrosive chemicals that they use.

In contrast, what they’re using in the oil service companies is probably not nearly as volatile. In the oil (production) business, everything is heavy and expensive, you know. So it’s likely that durability and strength may be more important than actual chemical resistance for the oil service companies. You know most of the stuff they use gets cleaned off with diesel fuel.

You certainly don’t want to get it on your hands, but it’s not nearly as strong as the chemicals that they work with down in the Gulf of Mexico where all the refineries are, you know. They do use lots of plastic-coated piping etc. to hopefully help make things last a little longer. But yeah, I think that definition is probably fine; oil refineries and service companies.

What Critical Role do Refineries Play in the U.S. Energy Market?

Formaspace: Maybe we should take a step back and ask you some very basic questions. Some of our readers are not from Texas, and therefore, may not know how a refinery is able to make refined products, such as gasoline, from crude oil. Can you give us some background on what refineries do and what their needs might be as far as laboratories?

Flynt Gaines: Well, first of all, the natural gas products are probably separated from the crude oil long before it gets to the refinery. There are usually gas processing plants all along the pipeline system. Methane, ethane, and propane are very light, and they rise up (making it easy to separate before the refining process).

Regarding refining the oil, some products like Permian crude oil are very ‘light,’ making it easy to create gasoline. Heavier crude oil is used for making diesel, and the heavier still can be made into home heating oil. You can make asphalt shingles and road material from the very heavy stuff. Heavy and light refer to the ‘gravity,’ e.g. specific gravity of the product.

When you get down to the refineries along the Gulf of Mexico, they can refine oil with a higher viscosity. At the core of these refinery operations, you use a catalytic conversion unit to break (or “crack” in industry jargon) the hydrocarbon molecules down. The product is run through the catalytic converter — the lighter material rises up, and the heavier distillate goes to the bottom.

Formaspace: So it sounds like the testing laboratories at refineries really would need chemically resistant laboratory furniture.

Flynt Gaines: Yes.

Complex Downhole Drilling Processes Managed by Oil Service Companies

Formaspace: As we mentioned earlier, the other market sector within the oil and gas industry we would like to target is oil service companies. We’ve already been successful at creating a custom workstation for Schlumberger, which they use to repair pipes and tubes, a.k.a tubulars, used in downhole drilling operations.

Flynt Gaines: Well, Schlumberger is definitely one of the biggies in the pressure pumping side of the business.

Formaspace: Yes, thanks! Could you give us some insights on how oil service companies go about their job in performing the downhole drilling process? From our understanding, they send a drill bit down the hole, along with a pneumatic percussion mechanism (the ‘hammer’) that pounds the drill bit into the rock to break it up.

Flynt Gaines: Right. And as you’re drilling down, you’re going to encounter pressure. To counteract that, use your drilling mud, which helps you hold the well back and prevent a ‘blowout.’ You’ve also got a blowout preventer (”BOP”) at the surface. The BOP will hold back a lot of pressure, but the drilling mud is very important too. And as you may know, you can have anywhere from 14 to 17 pounds mud, and it can vary for deeper or higher pressure formations.

And, in addition to controlling the well pressure, drilling mud helps bring the shards of rock (created by the drill bit) back up to the surface. The way it works is the fluid is forced down the middle of the drilling pipe, where it shoots out around the drill bit and then carries the remnants of the broken rock to the surface, and that helps you keep moving.

It’s just a good idea to map out the whole process as you’re drilling so that you know what you’ve drilled through – it gives you a lot of information.

My engineer will be at the surface watching everything. He knows how long it takes to get from 10,000 feet to the surface, so he’ll look at those rock remnants through a fluorescent light to see if it’s soil-bearing rock, etc., in order to map the type of rocks that they’re drilling through. That helps you know the porosity of the rock, which is very useful information for processes, such as fracturing, for example.

You’re also going to compare the notes from your mud engineer with the readings from your electronic log taken inside the borehole. That way you can say something like ‘Okay. Yes. It looks like this is an oil-bearing rock, or there’s a lot of water in this rock, or this is a high-porosity area, or this is a granite that will not give up anything.’

Formaspace: Do the drill bits themselves take these electronic measurements and send them to the control room?

Flynt Gaines: That’s close, but the drill bit itself won’t tell you anything. The drill bit is like a sledgehammer. I mean, it is just cracking rock. But you can have more sensitive equipment mounted a couple of feet up that can send out the data. This process is called Measurement While Drilling or ‘MWD’ for short, or sometimes Logging While Drilling (LWD).

Formaspace: How long do these down the hole drilling operations take?

Flynt Gaines: In this industry, we work extremely long hours, and when we talk about a 24-hour job, you know, the wife may think you’re going out there for 24 hours. No, that means you’re on site 24 hours a day.

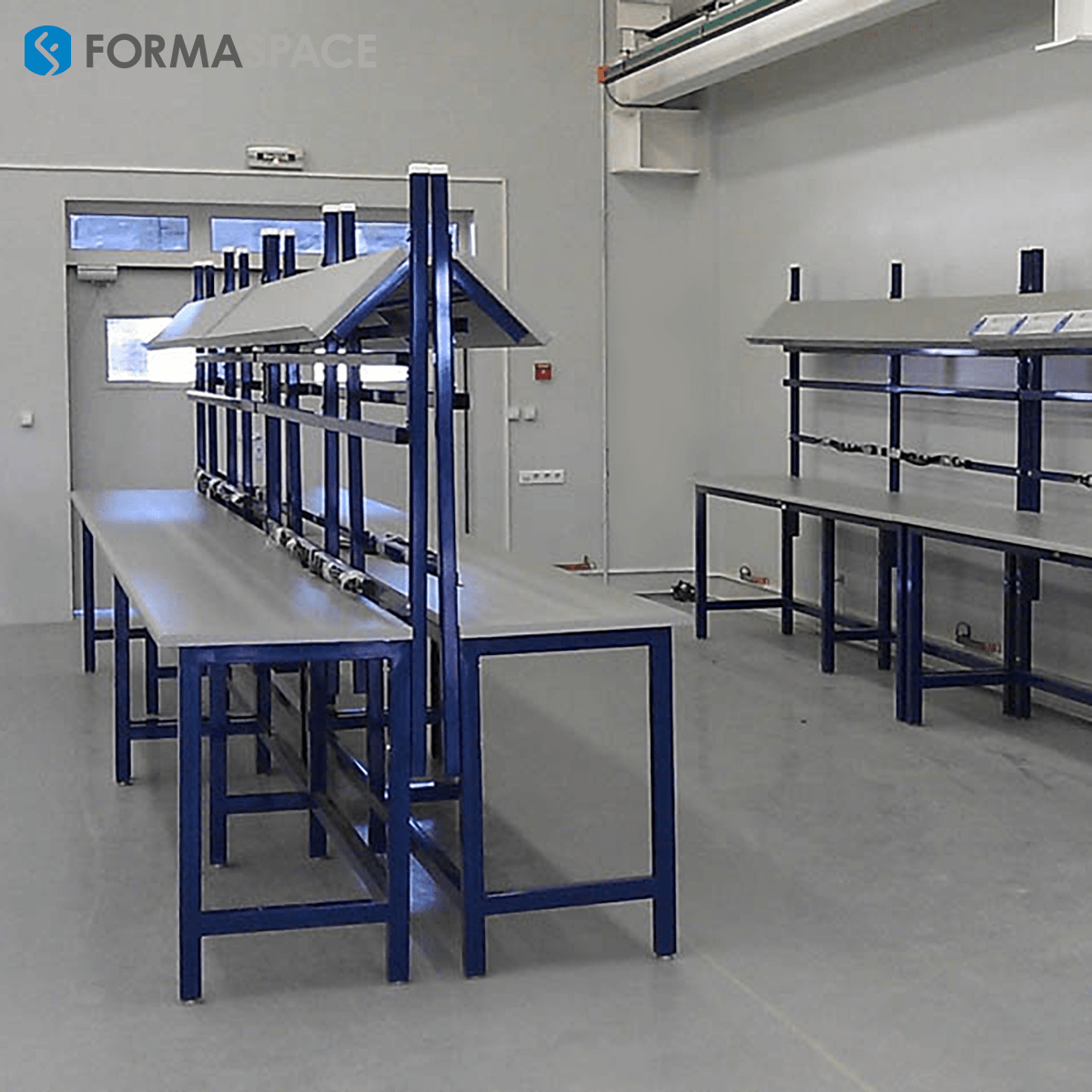

When I was with the operator, we would often use pressure pumping companies like Baker Hughes, Halliburton, and Schlumberger. And you know, they had everything. I mean they brought in their 23 men crew, all the pressure pumping trucks, the lab. They had everything.

I’d go out there, thinking we might hit total depth on a Tuesday, so I’d bring several days of clothes, maybe a little food. But because we have some hard drilling, we don’t hit until Friday.

Meanwhile, everybody has been out there all that time waiting for you to hit your total depth. Particularly those guys that are sitting there watching the monitoring equipment. I mean, they’re working. Most of those guys will work 12-hour shifts and then they’ll go – there’s kind of a sleeper room where you can go sleep while you’re off and you go back.

So I’m thinking that comfort is important when using the equipment. Remember, you’re mostly dealing with heavy equipment, high pressure, lots of horsepower in that equipment, so you have to be alert. You know, people can get hurt.

Portable Labs Used to Evaluate Drilling Samples

Flynt Gaines: I’m thinking in terms of furniture now, and I just thought on an insight for Formaspace. We usually have a little portable building that we have to roll it out to a drill site. Inside, there is a small laboratory where the ‘library’ of samples are stored and interpreted. That would be a good target laboratory market for you to go after.

Formaspace: Thank you. Can you tell us what tests are performed and how are these configured?

Flynt Gaines: Sure. When you’re having this drilling mud come to the surface, you’re running it through some drill shaker screens, which filter out the mud, leaving the extra hard rock. The mud engineer scoops it up, takes it inside into his own lab, and looks at it through a fluorescent light to see what he’s got.

There’s a librarian working there too, who marks the depth of each rock sample. He keeps track of all the samples of different rock pieces, which will subsequently be used for analysis.

Formaspace: What kind of equipment layout do they have inside these portable trailers?

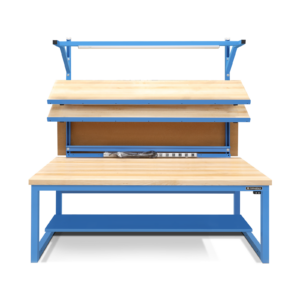

Flynt Gaines: I believe they use chemically-resistant stainless steel throughout. They would always mount the computers and the monitors up high so that no chemicals would get on them. And of course, since they’re mobile, everything’s mounted very securely to avoid damage in transport. The workstation area was at waist height, with storage mounted underneath to keep the samples secure.

Remote Monitoring Control Rooms

Formaspace: Aren’t there control rooms used to monitor these drilling operations as well?

Flynt Gaines: Yes. In fact, at Petromax, we were one of the first small companies that had a live camera at the drill site that allowed us to log onto the Internet and check at any time of the day to see how things were going. And that was just partially for curiosity, but also to just kind of monitor progress. Oftentimes, the camera provided us with more specific information than the verbal reports from the field.

Of course, today, Houston (where the major oil company headquarters are) is full of control rooms, and you will have live data feeds that go from the wells back to these control rooms — especially those sites that have multiple wells drilled at the same time.

Environmental Safeguards at Wellheads

Formaspace: Do oil and gas companies usually have an environmentally conscious operational policy? Are there any standards or legal requirements for improving environmental footprint?

Flynt Gaines: You know, everybody thinks that oil and gas companies are a kind of scorched Earth people. I think that for the most part, that’s not true.

For example, when we drill a pit to handle our water and mud, we’d line it with a plastic. Two reasons. One, we don’t want a lot of absorption, you know, stealing the water we want to use. And another is to prevent contamination. After we finish with the drill site and everything’s pulled away, that water is pumped out, the plastic is removed, and that pit is leveled over so you can’t tell there was a drill right there.

In general, we try to remediate the damage that we’ve done as we pull away. For one thing, these surface owners, we want them to continue to welcome us, because if that was a successful well, we might want to have a twin 400 yards away, and we don’t want them to be resistant to us coming back. And two, if I’ve poisoned their cattle, you know, they’re not happy to see me. So we try to be good neighbors.

We have usually 400-barrel tanks connected in a series, called a tank battery, where the oil is stored temporarily. We also put containment pits around the tanks. Around that tank battery, you will have a berm that will hold at least half as much as the tanks will. The reason we do half is that you never let the tanks get full. Once you have a well producing, and it’s putting oil in the tanks, you’re running trucks out to drain the oil out of those tanks and take it to market. So if there was a rupture of a tank and it was to spill, that berm will hold the oil. And so you’d have a small area that is exposed to the oil instead of it running down the hillside to the creek. But that’s just kind of a standard practice. I mean, we do that. You set the tanks; you build the berm around it to contain any possible spill.

Another thing we have is we worry about when you produce a well, there’s water that comes up with it, and that’s not good water. That is salty water. So a spill will make a salt deposit on the surface. So, again, you don’t want that to happen. So you will have sensors in your team, so when your tank is getting full, your sensor tells the pumping unit, “I don’t have anywhere to put any more water.” And so your pump will shut off because you only have so much capacity. And you usually have a pumper employee assigned to each well, and he goes around and he checks the condition of the meters, all the tanks, and the processing equipment in the lines. And many wells are checked daily. And as time has gone, we’re starting to use more electronic monitoring equipment. But, yeah, a lot of them are still checked daily.

Formaspace: Workplace safety is also a big concern, right?

Flynt Gaines: Yes, safety policies are very important. You have to wear steel-toed shoes and a hard hat, and there are some fields that you have to wear fire retardant coveralls. And those will protect you in a flash fire. I mean, not forever, but, those will protect you, gosh, I believe it’s like 400 degrees. They just call it FR clothing. That’s just Fire Resistant clothing. And then there is a safety meeting every day at a drill site. Your new crew comes on. There’s a safety meeting that goes on before you climb on that rig. And basically, we’ll say, ’Alright, at this level, we had a gas kick.’ Or, you know, they just let you know what’s going on with the well. So, yeah, that’s standard procedure.

Peak Oil: When Will We Run Out of Petroleum?

Formaspace: We want to thank you, Flynt, for providing us these valuable industry insights. But we have one more question before we let you go: There is a lot of talk about peak oil, what is your view? When will we run of oil?

Flynt Gaines: We will never run out of oil. We have source bedrock that is still producing oil today. That source bedrock emits oil, which rises to shallower layers of rock and into the reservoirs. I think we are burning 100 million barrels of oil per day right now, so I’m thinking it will be less plentiful, but we will never entirely run out of a well because the Earth is still producing the oil.

Formaspace: Well that’s good to know. Thank you again for your time. We really appreciate it!

Partner with Formaspace

If you can imagine it, we can build it.

We have the expertise to build specialized furniture for the toughest markets in the world.

Our clients include many Fortune 100 and 500 companies, including most of the major oil and gas companies.

Want to learn more about how we can build a custom oil and gas laboratory solution for you at our factory headquarters in Austin, Texas?

Check out our free Formaspace Virtual Workbench Builder, which allows you to configure your workbenches online.

Then contact one of our friendly Formaspace Design Consultants to find out how we can customize our solutions to meet your exact specification.