As Covid vaccination programs across the country push forward to inoculate ever higher numbers of the American public, now is a good time to reflect on the current state of our health care system and consider what we could do to make it more effective and efficient.

That’s what makes a new academic work, Health Insurance Systems: An International Comparison, researched and written by Thomas Rice, a distinguished professor of health policy and management at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health, such a timely and important resource.

Rice has conducted a thorough investigation of the costs and health outcomes of ten nations, including the United States, making it easier to make direct comparisons between countries and to identify the best practices in public health policy and finance.

Having Survived Three Supreme Court Challenges, the Affordable Care Act is Now More Popular than Ever

We’ll look in detail at Rice’s findings shortly. But it’s also worth mentioning at this point that the current US health care system we have today appears to be with us in its current form at least through the remainder of the current Biden administration.

That’s thanks to a recent Supreme Court decision not to invalidate the Affordable Care Act (or ACA, for short and often colloquially known as ‘Obamacare’), making this the third and likely final attempt in recent years to overthrow the law in court for the foreseeable future.

Pollsters have found that the ACA has also become more popular over time, with an increasing percentage of Americans approving the law, including the Medicaid expansion portion. Public opinion values a couple of key provisions of the law, including keeping young adults up to the age of 26 on their parent’s insurance plans, the exclusion of discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, and the elimination of time or financial limits on treatment coverage.

But the new law has many of us asking, does it make health care insurance truly affordable? The premiums, even with Federal subsidies, are not cheap. And coverage is not available for impoverished residents of states that elected not to extend Medicaid coverage to their low-income populations.

On the other hand, the ACA did expand health care coverage for tens of millions who previously had no health care insurance, and its importance has grown as millions more were laid off during the height of the Covid pandemic lockdown.

The Biden administration has helped the situation by re-opening the health care exchanges at the beginning of this year, and also by raising the individual premium support payments made by the Federal government.

Democrats in Congress are also looking at ways to expand Medicaid coverage to poor residents in states that did not elect to accept Medicaid expansion, such as allowing cities, counties, and even individual health systems to participate in Medicaid expansion directly, effectively bypassing the recalcitrant state governments.

There are also efforts underway to provide dental, hearing, and vision coverage the Medicare recipients (e.g. the over 65s) for the first time.

On the other hand, while Biden campaigned on the idea of creating a public option for the ACA health exchanges (in an attempt to drive down insurance costs), this idea remains on the back burner for the moment.

But is the ACA Enough? We still pay far More for Health Care than Other Industrialized Countries

Increased subsidies and improved coverage plans might help stem the tide of seniors traveling over the border for discount root canals in Mexican dental offices or riding busses into Canada to buy cheaper prescription drugs – both of which were common practices prior to the pandemic.

But is it enough?

The concern that we are spending too much on health care, as individuals and as a government, is based in fact, according to Rice’s research. He writes that US per capita health care spending is nearly double that of the nine other leading industrial countries he studied, e.g. the UK, Canada, Sweden, Australia, France, Japan, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands.

Rice also points out the US annual spend on health care consumes 60% more of our GDP when compared to these other countries.

Expressed another way, Rice estimates the US spent $3.5 trillion on health care in 2017, which represents 45% percent of the total world spending on health care, an amazing feat considering the US population is only 4% of the world’s total!

These increased costs here at home are born out in the higher prices paid for drugs and medical procedures.

For example, the delivery of a baby costs on average $11,167 in the US, while the same delivery in the Netherlands only costs $3,638. Similarly, a dose of the breast cancer drug Herceptin costs $211 in the US but only $48 in Germany.

It’s no wonder that Rice found that 1/3 of Americans reported they faced cost barriers to getting timely medical care during the previous year.

It’s no wonder that medical debt has long been the leading reason for personal bankruptcy in the USA, and analysists now estimate that $45 billion in unpaid medical bills have been sent to collection.

(To help alleviate this issue, a group of Democratic Senators has proposed the Medical Bankruptcy Fairness Act of 2021 to help address the number of bankruptcies expected as a result of the financial hardship caused by the Coronavirus pandemic.)

Are We Getting Better Care for All the Money We Spend? According to Rice, Most Health Care Statistics Say NO…

The next question is whether we are getting better results thanks to our increased spending on health care in this country.

Unfortunately, the answer is a definite NO, according to Rice.

Several key metrics tell the discouraging story of worse health care outcomes in the US:

The first is a comparison of mortality from preventable causes, e.g. cases where timely medical care should have been able to help prevent death.

On this basis, the US is in last place among the ten countries studied – we had 175 mortalities per 100,000 population – a figure that’s twice as bad as Switzerland.

The same story is true for mortalities from treatable diseases; here, the US suffered 88 mortalities per 100,000 patients, while Canada had far fewer, only 59 per 100,000 patients.

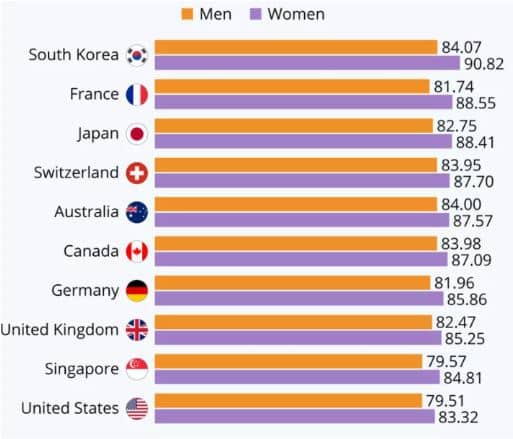

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization reports that the US has fallen significantly in projected life expectancy; by 2030, Americans can expect to live to 83.32 years (female) and 75.51 years (male), but that puts us behind Singapore, the UK, Germany, Canada, Australia, Switzerland, Japan, France, and the new leader, South Korea, which is projected to have a life expectancy of 90.82 years for women and 84.07 years for men by 2030.

Given our High Health Care Spending, do we at Least Have Better Access to Primary Care Doctors?

According to Rice, having ready access to a primary care doctor is another major issue in the American health care system – despite our higher spending.

Despite the ACA helping tens of millions of Americans get health care insurance, there is still a substantial gap in coverage – a 2019 study estimates that 9.2% of Americans still don’t have access to health care insurance coverage, which represents just under 30 million people.

Equal access is also an issue, something that many individuals who moved to rural locations to work from home (WFH) during the Covid pandemic have found out – many rural areas are virtual health care deserts due to the many small, private hospitals that have closed over the past decade.

Urban areas also have major disparities, with fewer doctors serving underprivileged areas, according to Rice.

Contributing to an overall shortage of primary care doctors is the fact that so many US practitioners elect to become specialists rather than general physicians. Rice estimates that 2/3 of US doctors are specialists – likely due to the higher prestige and incomes associated with specialty practices. This skew toward specialists makes the US a distinct outlier from the other nine countries Rice studied, where the percentage of general primary care doctors is consistently 50% or higher.

So Why is the Cost of Health Care so High in the USA, and How Can We Get Better Outcomes and More Value for our Money?

How to fix our health care system is the multi-trillion-dollar question.

It’s not only a complicated, patchwork system – one that many aptly describe as the ultimate Gordian knot – it’s also a problem that’s fraught with political discord.

Indeed, if we’ve learned anything from the Covid pandemic, it’s that health care has become one of the most politically divisive arguments of our time.

We only have to look at the recent battles over masks to prevent the spread of Covid, or the large percentage of the people who believed the Coronavirus was a government conspiracy (eg. plandemic) – to see how difficult it will be to improve things.

Nonetheless, we will attempt to wade into the issue at our peril to identify some of the main arguments and whether we can learn from the best practices of other countries that Rice has identified in his research.

Argument 1: Our Fragmented Health Care System Makes It Difficult to Achieve Efficiencies of Scale — True or False?

One thing that we can probably all agree on is that no one would propose re-creating the current US health care system if given the chance to start with a clean sheet.

As Rice reports, we are a true outlier in the world, particularly due to our practice of relying on employers to provide nearly half of our health care, an unusual practice that dates back to a wage freeze workaround during the Truman administration (when union leaders demanded higher wages but were given new health care benefits instead as an alternate form of compensation.)

It’s not difficult to see how overly complex the system is when you look at the number and variety of health care programs currently available in the USA:

- ACA subsidized health care insurance

- Charity sponsored health care for the indigent

- Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- Concierge health care plans

- Employer-based group coverage

- Group-based private health care insurance

- Individual private health care insurance

- Indian Health Service

- Pension-based health care plans

- Medicaid for lower income

- Medicare for seniors

- Medicare Advantage

- Social Security Disability

- Short-term individual insurance

- Teacher pension health care plans

- Tri-Care for armed forces personnel

- Veteran Health Administration for veterans

To simplify analysis, Rice organized these healthcare plans into four categories:

- Employer-based coverage: 46%

- Medicaid 27%

- Medicare 18%

- Individual coverage 7%

Looking at it this way, it’s easy to see how fragmented our health care system is.

It would take major new reforms, such as switching everyone over to a private insurance program or instituting a single-payer system (used in the UK, Canada, and Australia, for example, as well as our own Medicare and Tri-Care programs, to name a few), to achieve significant cost efficiencies in our health care system.

But such a radical overhaul would require a major unwelcome change for over half of the population, a very unpalatable idea from a politician’s point of view.

Yet, the fact we have so many different healthcare programs running in parallel makes us strikingly different than the other nine countries, which, according to Rice, have one system that’s available to all, which makes it much simpler to manage and wring out efficiencies in the system.

Verdict: True

Argument 2: Health Insurance Companies are the Reason We Pay So Much for Health Care — True or False?

Many health care reform activists point to the large profits of health care insurance companies as proof that insurance-based systems are inherently inefficient and should therefore be replaced with something like a single-payer system.

Yet Rice found that private health insurance systems work very well in the Netherlands, where all health care is managed and reimbursed by private insurance.

However, Rice points out there are some salient differences in the Netherlands. Over there, the insurance companies are all required to offer the same health benefit packages, so the competition is on who can offer the best price and best customer service. Another factor is that non-profit insurance companies also compete with private ones. Nonetheless, competition among insurance companies is strong and the Dutch enjoy a choice among companies.

Verdict: a qualified False

If managed correctly, insurance companies can provide a valuable service without driving up healthcare costs.

Argument 3: The US Pays More for Medical Innovations and Ends Up Subsidizing the World with Our Discoveries — True or False?

There is truth to this assertion.

The US does benefit greatly from the innovations created by leading Pharma companies and health care entrepreneurs that offer American patients many of the world’s leading-edge clinical treatments and medical devices – and they, in turn, benefit from higher reimbursements for their products and services than in other parts of the world, as well as an active capital market to fund expensive research programs and startups.

New drug discoveries and other clinical treatments introduced in America often take longer to make their way overseas, where strong financial oversight by health care system managers often results in deep discounts to gain access to a national market.

As a result, the US health care system does lead the world in new treatments, and this seems to be reinforced by the high percentage of specialist doctors here in America, which comes to about two-thirds, as mentioned earlier.

Year after year, the pharma industry lobbies Washington to stop efforts to introduce price controls on prescriptions or to prevent the CMS from negotiating with drug companies over reimbursement rates – which is a common practice in Canada and the UK, for example, and helps explain the lower prices they pay for drugs.

Verdict: True

Argument 4: As Americans Get Older, We Need to Address the Growing Shortage of Primary Care Doctors — True or False?

For decades, many Americans have taken for granted their local, sole proprietor primary care physician.

But increasingly, that Norman Rockwell vision of a doctor providing family medical care is going the way of doctor house calls.

As baby boomer physicians retire, they are often closing up their local doctor’s office for good, as younger physicians choose to avoid the long hours, low reimbursement rates, high insurance costs, and general aggravation of running a small business in favor of employment contracts at larger healthcare institutions, which offer regular hours, steady pay, and paid vacations.

Among the sole-proprietor doctors who choose to remain in business for themselves, many are now aligning themselves with so-called concierge medicine programs, which bypass government-subsidized patients (such as Medicare and Medicaid patients) in favor of more well-heeled patients who can pay a fee (often upwards of $2,000 annually) for better access to their doctor.

These consolidation trends, along with the tendency of American doctors to choose a specialty over general practice, are now colliding with a patient demographic that’s growing much older – and older patients need more care than younger cohorts.

What can be done?

Some point to the uptake in telemedicine, which took off during the pandemic, as part of the solution.

So-called “physician extenders,” e.g. physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs) who can prescribe medications, and medical scribes (who enter patient data into EHR systems) are increasingly used to supplement the efforts of primary care physicians, who may be called upon to see as many as two dozen patients per day.

There are also financial incentive programs to encourage doctors to relocate to underserved rural areas.

Increasing the supply of new doctors is also on the agenda, as states build new medical schools and, in the state of Texas, experiment with a fast-track education model that shaves a year or two off the traditional MD education program.

But the core of the issue may be the low reimbursement rates offered by the Federal government’s CMS agency for seeing Medicaid/Medicare patients. These low rates, which were once considered a “floor” reimbursement rate in the industry, are increasingly seen as a “cap” by health insurance companies, effectively driving down patient reimbursement rates across the board.

Verdict: True

Argument 5: We Need to Pay Doctors for Outcomes, Not for Procedures — True or False?

As Rice points out, the American health care system is unique in its Fee for Service (FFS) model, unlike other countries that compensating physicians and hospital systems a fixed rate for good health outcomes.

Of course, this has been a point of discussion for decades, and the ACA law took some baby steps toward addressing this issue by offering incentive payments to physicians and hospital systems that had better health outcomes and/or used fewer expensive diagnostic tests.

(They also instituted heavy penalty fines for errors, such as when patients need to be readmitted to hospitals to treat hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) shortly after being discharged.)

However, doctors found the rules to earn the incentives to be very cumbersome, as the CMS required even more paperwork to document the “meaningful use” of health care provided to each patient (to avoid fraud), leading many physicians to conclude the financial rewards were being eaten up by increased administrative costs.

Consultants, such as those from McKinsey, have long advocated making a complete switch to an outcome-based reimbursement scheme, one they contend would make the overall health system more efficient.

As Rice points out, this approach does work overseas, but he cautions that in countries that apply overall spending caps (such as the UK and Canada), there can be longer waits for non-urgent treatments – in other words, a rationing of care, an idea which is anathema to the US public at large.

Verdict: Possibly True

If managed correctly, reimbursements based on outcomes would be more efficient; however, this approach could lead to health care rationing if strict budget caps are put in place.

Argument 6: We can Save Money by Moving Care from Expensive ERs to Where People Are, Using New Technologies and Logistics Programs — True or False?

One of the key arguments made when the ACA was debated in Congress was that increasing insurance coverage rates among the American population would, in turn, reduce the number of ER visits – the thinking being that insured people could make a less expensive visit to their physician, which would be covered by their new insurance plan.

This, however, did not pan out the way ACA health care advocates had hoped; ER visits have remained stubbornly high, which has a disproportionate drag on overall health care budgets.

Some cities, such as Houston, have tried innovative programs to reduce ER visits (remember each trip to the ER can tie up a police patrol car, fire truck, or ambulance for hours at a time while they wait for the patient to be admitted) by providing first responders with telehealth video tablets that allow 911 callers to be evaluated in the field by a doctor at a remote medical facility, who can determine whether a lower cost taxi or Uber ride to a less-costly urgent care facility is in order in lieu of a trip to the ER.

That is just one example of using new technology to reduce our dependence on ER visits.

Other innovations are taking place as well to put health care in more convenient locations, from so-called “doc in a box” doctor’s offices in stores such as Walgreens or Kroger to the long-term plans of e-commerce logistics giant Amazon to up-end the pharmacy market with its recent acquisition of digital pharmacy PillPack.

Verdict: True

Argument 8: We Can Reduce Health Care Costs by Introducing Limits on Malpractice Lawsuit Payouts and Allowing Health Insurance Coverage across State Lines — True or False?

States such as Florida and Texas have introduced liability limits on medical malpractice lawsuits, and it’s widely understood that this has encouraged a higher number of specialists (ranging from plastic surgeons to heart specialists) to locate in these and other states that have tighter limits on malpractice lawsuit payouts.

Does this this kind of tort reform lead to reduced spending on health care?

A 2017 study published by the NIH on the impact of medical tort reform in Texas found that, in the aggregate, the public did not see any appreciable reductions in the cost of health care.

Another widely held belief is that relaxing state rules governing health care insurance could lower health care spending by allowing insurance to be sold over state lines.

One justification for this idea is that larger patient pools would lead to greater efficiencies; however, there is little evidence that the largest states (California and Texas) that already have huge populations enjoy lower rates than other smaller states.

Critics of this approach believe it would lead to a “race to the bottom” as a few states would try to attract health insurance companies to set up shop in their states by offering minimal regulatory oversight.

Verdict: a qualified False

The Bottomline: We Need to Make Health Care a Priority

It’s not hard to conclude that reforming our health care system is a daunting challenge.

Is there a secret that other countries share?

According to Rice, there is.

He believes that the other countries got off on the right foot by first committing to offering universal health coverage for their citizens.

This makes it easier to come up with innovative health care solutions, such as intervening as needed (by negotiating and setting prices, for example) when market forces aren’t capable of controlling fees.

Rice adds that he appreciates that our country’s view of “American Exceptionalism,” a belief that’s based on deep skepticism of government intrusion into our private lives, is the primary reason that changing our health care system is so difficult.

But he adds that, if we chose to, we could apply the “lessons learned” by other countries and enjoy a more efficient health care system that would:

- Offer everyone more equitable access to care

- Create a simpler, unified healthcare system that promotes fairness and efficiency

- Save money by allowing the government to engage in planning and allocating resources

- Apply cost-effectiveness tests to evaluate benefits versus costs, especially in pharmaceuticals

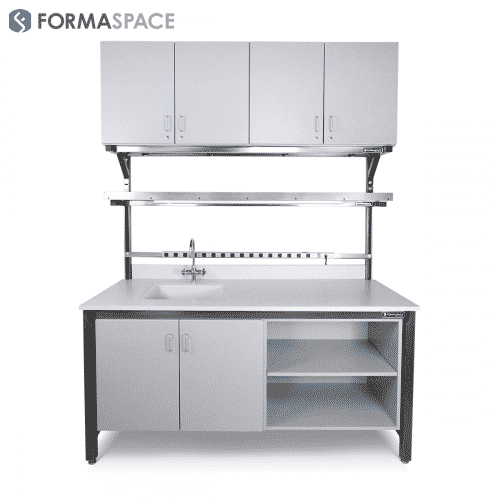

Formaspace is Your Partner for More Efficient Health Care and Laboratory Facilities

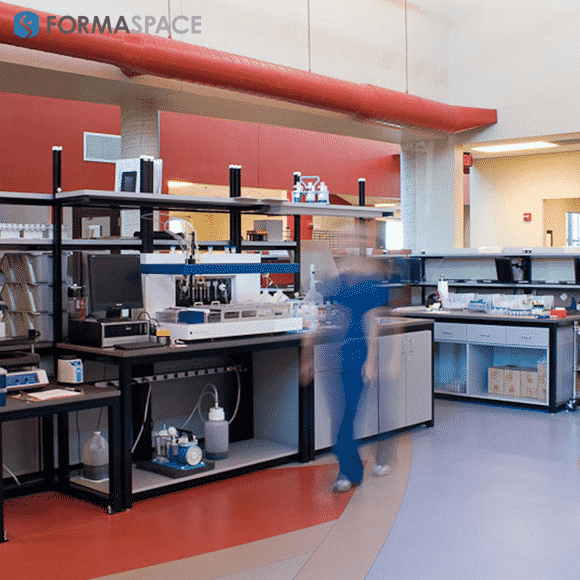

Turn to Formaspace when it’s time to upgrade your existing facilities or break ground on new clinical and research laboratories, university classroom and labs, or pharma manufacturing facilities.

If you can imagine it, we can build it, here at our factory headquarters in Austin, Texas.

Make contact with your Formaspace Design Consultant today and find out how we can work together to make your next project a success.

You will see why leading health care companies and research institutions, such a Roche, GingoBioWorks, Metrohm, and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub choose Formaspace.