Wastewater-Based Epidemiology (WBE) puts Water Testing Labs at the Forefront of Infectious Disease Detection and Control

Water testing laboratories are at the front line of defense in public health. In this Formaspace laboratory research article, we look at the challenges facing water testing laboratories in performing vital Wastewater-Based Epidemiology (WBE) services.

· Testing for Polio Virus in Wastewater

Polio is in the news again thanks to its recent discovery in New York and the UK. The problem may yet get worse – due to disastrous flooding in Pakistan, one of two countries (the other being Afghanistan) where polio is not yet under control.

Water testing laboratories have been screening wastewater for the paralytic poliomyelitis virus, which causes polio, using methods dating back to the 1940s.

In the virus detection method approved by the UN, sewage samples are collected at wastewater treatment plants and mixed with dextran and polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymers to separate them. Any enteric viruses (including polio) will collect 50-100x higher concentration levels at the bottom and the boundary (interphase) layers. These samples are then eluted to further isolate the virus samples. Finally, these are applied to L20B mouse cell cultures to identify any presence of the polio virus.

Thanks to these wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) protocols, public health officials were able to confirm the unexpected presence of poliovirus in Greater London, then in Rockland County, New York, just north of New York City. This is big news, as the US was declared free of Wild Poliovirus (WPV) in 1979.

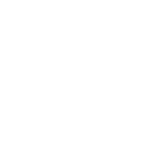

The virus found in New York was cVDPV2 (circulating Vaccine-derived Poliovirus type 2), a variant mutation derived from the live, attenuated (e.g. weakened) oral polio vaccine, known as Sabin OPV. Though Sabin OPV was the first polio vaccine, it’s no longer widely used in Western countries, having been replaced with the Salk inactivated vaccine (IPV), an injectable version of a killed polio virus that cannot mutate and spread.

However, Sabin OPV (including the most current version, Sabin OPV serotype 2 or mOPV2) remained the preferred option for polio eradication campaigns in developing countries for decades due to three factors: its low cost and ease of administration (no injection needles are required), its ability to pass protection from a vaccinated individual onto other family and community members, and its capability of halting active polio outbreaks by preventing the virus from entering the intestinal lining of vaccinated individuals.

The downside of Sabin OPV is there is always a small chance that the virus can mutate to create neurovirulent variants (such as cVDPV2) that cause neurological disease. While the number of these cases remains low (in the hundreds), travelers can bring these variants to areas where polio has been eradicated, places where vigilance (and vaccine rates) are now low.

Indeed, the New York cVDPV2 outbreak is thought to have come about from an individual (or family) arriving from somewhere in the Middle East, possibly via Israel. NYSDOH’s public health laboratory, Wadsworth Center, confirmed the presence of cVDPV2 in sewage samples via a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, and now it’s up to public health officials to trace and contain the outbreak in Rockland County, where vaccination rates among the Orthodox Jewish community are considered too low to create effective herd immunity.

To stop the spread of cVDPV2 at the source, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded the development of a next-generation version of the Sabin OPV serotype 2 (mOPV2) oral polio vaccine, called novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2). Over the last two years, the WHO has administered over 110 million doses of nOPV2 around the world as part of an emergency use authorization with good results. The new nOPV2 vaccine uses genetic engineering techniques to modify the Sabin sero type 2 RNA gene sequence so that it’s more stable and less likely to create variants that cause neurological disease.

· Testing for Covid Virus in Wastewater

The sudden emergence of the novel coronavirus Covid 19 in early 2020 once again thrust water testing laboratories into the forefront of public health – this time challenged to:

- Identify the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA (the virus that causes Covid) in sewage effluent

- Correlate the concentration of virus found in the waste stream with active Covid infections

- Help determine if the virus can be spread enterically, e.g., by ingesting contaminated sewage

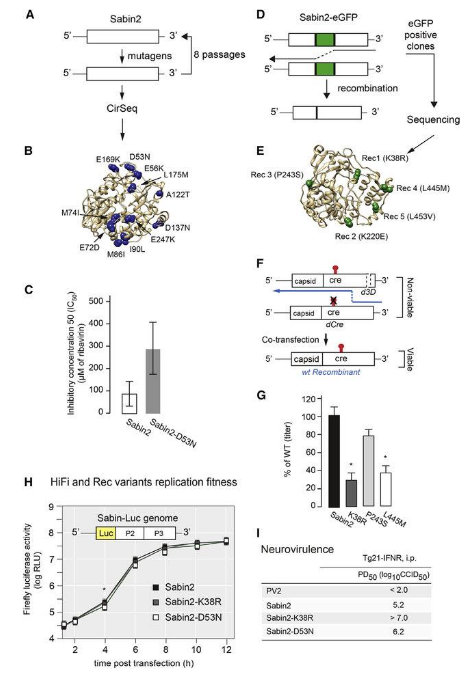

- Identify concentrations of specific Covid variants, such as Delta or Omicron.

Water testing laboratories were able to draw on their long-standing expertise in testing sewage samples for the presence of the poliovirus.

However, in practice, testing for the Covid virus required creating new lab techniques.

For example, collecting Covid virus samples proved more difficult due to the small size of Covid RNA fragments, so several methods were devised, including using electrostatic charges on filters to attract the virus, taking samples from concentrated sewage sludge, or using new collection devices containing magnetic beads or cotton swabs to trap the virus over several days.

Because the Covid viruses that are collected are highly degraded, most labs have turned to quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to amplify the small concentrations of Covid virus particles to identify key sequences within the overall original gene. As new Covid variants have arrived, these tests have had to be modified to find new unique characteristic genetic markers.

Epidemiologists looking at the Covid RNA fragments found in sewage have come to believe that it’s an unlikely vector for enteric infection – though water treatment workers should continue to take precautions.

Extrapolating the number of active Covid cases from virus concentrations measured in sewage has proved more difficult than anticipated. For example, heavy rains draining into sewers can cause the Covid virus concentrations to drop off, so some labs adopted the presence of pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) in wastewater as a useful proxy for quantifying the number of people passing stools into the sewage system at any one time.

This approach helped manage and normalize the data, but, unfortunately, later research determined that the rate of Covid virus shedding varies tremendously from one person to the next (by as much as a factor of 10), so water testing laboratories haven’t been successful in extrapolating the exact number of active infections from sewage samples; however, they can provide large trend analysis which has proved very useful to public health officials.

· Testing for Monkeypox in Wastewater

Monkeypox is the latest communicable disease threat facing the US.

Once again, public health officials have turned to water testing laboratories to identify the presence of the virus in sewage treatment systems.

Unlike Covid, Monkeypox is a DNA-based virus that is significantly larger than Covid and poliovirus.

Despite this key difference, laboratories report that water testing techniques developed for Covid RNA viruses seem to be working equally well for Monkeypox DNA viruses – the same RT-qPCR test equipment can be used for both, albeit with different primer setups tuned to match the virus being tested.

Across the country, wastewater surveillance has been able to pinpoint the “arrival” of Monkeypox in the community.

For example, UCSD researchers working with the wastewater stream in San Diego (with 2.2 million customers) first identified a positive result for Monkeypox on July 10, 2022 – at just over 10,000 viral copies per liter of wastewater. By August 2, the concentration levels in one liter of wastewater had grown to nearly 190,000 copies of the virus.

This research has helped public health workers anticipate the scale of community infection, and indeed by the end of August 2022, the number of known Monkeypox cases in San Diego County had nearly tripled to 270 cases.

Nationally, the CDC reports nearly 20,000 cases of Monkeypox across the US as of September 02, 2022. After a sharp rise in July, new cases have leveled out and will hopefully decrease, thanks to increased awareness of the disease and campaigns to vaccinate vulnerable populations with the Smallpox vaccine Jynneos, which also helps prevent Monkeypox transmission.

Fingers crossed, Monkeypox will not follow in Covid’s footsteps which saw one variant after another emerging over time. Researchers believe this is less likely with Monkeypox due to the fact it is a more complex DNA-based virus.

Nevertheless, water treatment laboratories need to be ready to meet the challenge of this epidemic as well as the inevitable diseases emerging in the future.

Formaspace is your Laboratory Research Partner

If you can imagine it, we can build it, here at our Formaspace factory headquarters in Austin, Texas.

Now is the time to talk with your Formaspace Design Consultant to get the latest insight on how to make your next laboratory build or remodeling project a complete success.