Recently, there has been intense interest in the use of Liraglutide and Semaglutide class drugs – with social media influencers promoting these drugs as a “miracle weight loss” solution.

In response, demand for these drugs has spiked to unprecedented levels, leading to widespread shortages of some formulations of these drugs.

In this Formaspace laboratory report, we take a look at how these “miracle drugs” work and how they have evolved to address diabetes and weight management.

Urgent Need to Address an Epidemic of Diabetes and Obesity

First, a little background on the need for better therapies to control diabetes and obesity.

Diabetes is a major health crisis in the US, with nearly 1 in 10 Americans suffering from the disease. Another 96 million Americans (nearly 1 in 3) have prediabetes and are likely to develop Type 2 diabetes unless they can reverse course by losing weight and/or controlling their sugar through improved diet and exercise.

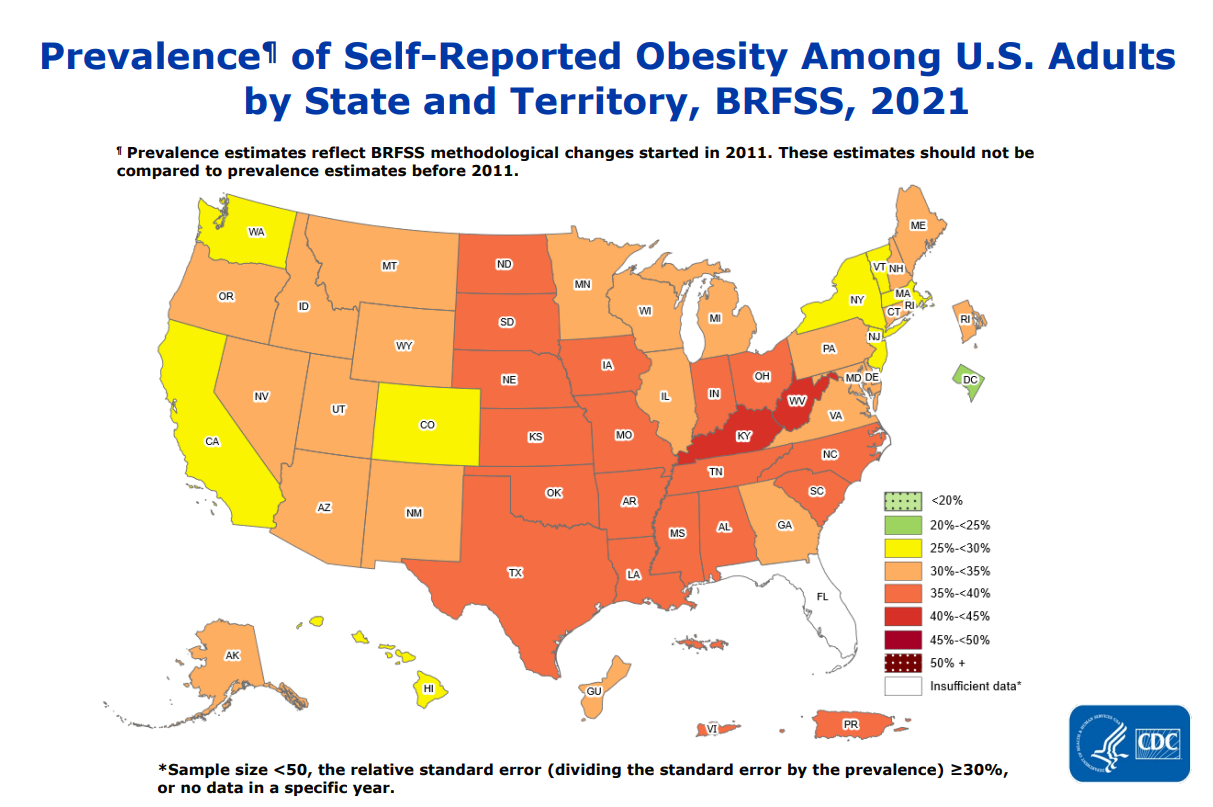

Obesity is a major risk factor for Type 2 diabetes, and obesity rates have been increasing year on year. As of 2021, some state populations are self-reporting obesity rates approaching 50%.

We can see the problem more clearly in this overlay graph from the CDC, which illustrates the correlation between the incidence of obesity and diabetes.

Mechanism of Action for Liraglutide and Semaglutide Class Drugs

It’s against this backdrop that researchers at Novo Nordisk sought to create a weight loss drug – one based on the replication and modification of hormones that control our desire for food.

The hormone they based their work on is acylated glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) – a natural incretin hormone produced in the small intestine that has a critical role in helping people maintain a proper weight.

When it’s working properly, GLP-1 regulates the amount of glucose in the body (by controlling insulin levels), it also delays gastric emptying (slowing down digestion), and adjusts our sensation of satiety, e.g. whether we feel hungry or not.

GLP-1 also reduces the production of the hormone glucagon, responsible for helping release carbohydrates stored in the liver as well as the creation of new glucose.

(Recent mouse-model research at the University of Pennsylvania has helped further our understanding of how GLP-1 hormones work – confirming they cross the blood-brain barrier to interact with a part of the brainstem known as the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), which helps regulate the body’s energy expenditure and food intake.)

Mimicking the Effect of GLP-1 Hormone with a Longer Lasting Drug Formulation

For diabetic and/or overweight patients, it would be ideal if we could simply increase the amount of GLP-1 hormone throughout the day – this would help them overcome the desire to eat more, digestion would slow down, and glucose and insulin levels would improve.

However, this approach has some serious limitations as the body’s natural (e.g. endogenous) GLP-1 hormone has a fairly short lifespan – the enzymes in our digestive system degrade GLP-1 (through peptidases), allowing us to feel hungry again several hours after we eat.

As such, using an unmodified GLP-1 hormone to control appetite would require multiple injection doses throughout the day – theoretically possible but not practical for patients outside of a hospital setting.

To get around this, drug researchers created a GLP-1 substitute – based on the human hormone GLP-1(7-37) – using DNA recombinant technology.

The resulting drug, Liraglutide, mimics the body’s (GLP-1) hormone, allowing it to essentially perform the same functions as a GLP-1 receptor antagonist.

Liraglutide also addresses the short lifespan of natural GLP-1 by adding a fatty acid chain to help slow its absorption and degradation, extending its half-life to around 13 hours post-injection, paving the way for patients to take the drug once a day. (Liraglutide is eventually broken down into smaller residues by proteolysis.)

The FDA approved Liraglutide for treating patients with type 2 diabetes in 2010, and it was brought to market by Novo Nordisk under the brand name Victoza. In 2014, the FDA also approved Liraglutide for helping obese patients (BMI greater than 30) to lose weight; for this label usage, Novo Nordisk introduced a formulation of Liraglutide under the brand name Saxenda.

Semaglutide Increases the Half-Life of Liraglutide from One Day to a Week

Building on the success of Liraglutide, researchers at Novo Nordisk sought to create newer versions that required fewer injections or could be administered orally.

To achieve this, they needed to develop a longer-lasting alternative that reduced Liraglutide’s metabolic degradation, thus increasing the drug’s half-life in the blood.

The new variant of the drug is named Semaglutide; it has a half-life that ranges between 165 and 184 hours, allowing it to be administered via injection once a week (instead of Liraglutide’s daily injection regimen).

(Novo Nordisk also created a non-injection version of Semaglutide that can be taken orally once a day.)

How was the half-life increased so dramatically?

With Semaglutide, the drug developers at Novo Nordisk modified the synthetic version of the GLP-1 hormone molecule in two locations, substituting arginine and 2-aminoiosbutryic acid for alanine and lysine at positions 8 and 34. These substitutions prevent dipeptidyl peptidase-4 from breaking down the molecule at position 8. The other change is that the lysine at position 26 has been acylated with stearic diacid. The fatty acid diacid chain binds well to albumin (blood protein), which helps it circulate in the body for a longer period, further helping increase the drug’s effective half-life.

The FDA approved Semaglutide in 2017 for diabetic patients, and Novo Nordisk brought it to market as Ozempic. The oral version was approved in 2019 and marketed as Rybelsus.

In 2021, the FDA approved another, higher-dose injectable version for weight management in adults – Novo Nordisk brought this to market under the brand name Wegovy.

One Drug Mechanism – Multiple Formulations and Brand Names

From a mechanism of action perspective, all of these brand name drugs (Victoza, Saxenda, Ozempic, Rybelsus, and Wegovy) are essentially variations of the underlying drug Liraglutide, only differing in their relative dosages, means of administration (e.g. oral versus injection) and their half-life.

As we mentioned at the beginning, there is huge public interest now in obtaining these drugs, driven in part by extensive marketing campaigns by Novo Nordisk that have been greatly amplified by social media influencers.

This Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) news report discusses how influencers (such as Kim Kardashian) have helped (directly or indirectly) drive up demand for Liraglutide and Semaglutide class drugs.

At the time of writing, the FDA reports on its Drug Shortages website that two versions of Semaglutide are “currently in shortage” – these are Ozempic (for diabetes therapy) and Wegovy (for weight management).

What’s Next on the Horizon: The Availability of Generic Version of Liraglutide in 2024?

Will Liraglutide and Semaglutide class drugs remain in short supply for the foreseeable future?

Given that the Denmark-based Novo Nordisk reportedly earned nearly $5 billion in 2021 sales for its Liraglutide and Semaglutide class drugs, it seems reasonable at first glance that they would find it in their economic interest to increase production to meet demand.

However, the answer to this question may be embroiled with what happens as the patents for these drugs begin to expire.

The patent for Liraglutide has reportedly already expired in China, and according to Novo Nordisk’s 2021 annual report, the first of Liraglutide’s patents will expire in Europe and the USA sometime in 2023.

(As we all know, pharmaceutical patents are a tricky business, and Novo Nordisk likely followed the traditional pharma playbook of patenting the drug for different uses over time, which would explain the repeated introduction of new brand names and claims.)

Nonetheless, several major generic drug companies are waiting in the wings to challenge Novo Nordisk with generic versions of Liraglutide once the patent runs out, including pharma giant Novartis’ generic subsidiary Sandoz, Teva Pharmaceutical, and Viatris (formerly Mylan).

Other companies, including Rio, Aurobindo, Sun, and Zydus, have filed applications with the FDA to produce generic versions of Ozempic (Semaglutide) when its patents run out.

The bottom line is that sometime in 2024, at least some generic version of the daily injectable Liraglutide will likely be available.

For insurance companies and patients who have been paying upwards of $1,200 a month for Victoza, the introduction of a lower-cost generic will be a welcome development.

Formaspace is Your Pharma Research Partner

If you can imagine it, we can build it, here at our factory headquarters in Austin, Texas.

Talk to your Formaspace Design Consultant today about how we can help make your next laboratory project or remodel a complete success.