As the omicron wave peaks in the US, employers are trying to identify new strategies to recruit and retain highly qualified workers.

But there is a lot of competition out there for the best talent.

The “Great Resignation” continues to be “a thing” — in December 2021 alone, over 4 million Americans changed jobs or left the employment market entirely.

That leaves nearly 11 million active job openings across the USA, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ recent surveys.

We’re currently gathering research for an upcoming article on how to make your recruiting and retention programs more successful given the current business environment.

One recommendation that stood out among others is the need to create an effective mentorship program, so we decided to break that out into its own topic and discuss it here.

So join us as we look at the top 10 key points to consider when creating and growing a successful mentorship program.

1. Could Academic Life Science Mentoring Programs be a Model for Businesses?

American business leaders often look wistfully at the success of overseas training and mentorship programs, wishing that we had something similar here at home.

For example, the German apprenticeship model is widely credited as a key contributing factor to the long-standing success of many German industrial companies.

And across Asia, the teaching profession is one of the most prestigious disciplines (often outranking doctors). Even the name teacher has special meaning and status; in Japanese, the word for teacher is sensei, represented by the kanji characters 先生, which signifies “the one who comes before” – an appropriate connotation for the act of handing down information from one generation to the next.

Here at home, many disciplines do employ long-standing formal mentorship programs. In law, young attorneys participate in internships, and some have the opportunity to clerk for judges. In the field of medicine, newly graduated doctors get hands-on training during residency, while young architects must complete thousands of internship hours as part of the Architectural Experience Program (AXP). And in the trades, those pursuing a career as a licensed electrician must first work their way up through a journeyman electrician apprenticeship program.

But what about other sectors of the economy that don’t have formal mentorship programs or legal requirements for training and certifying young people – is there a model that is appropriate in these circumstances?

We propose taking a look at the experience of mentoring young Ph.D. candidates in science as a model for establishing a mentoring program in industry sectors, particularly those in technology and STEM fields, from high-tech manufacturing to life sciences.

A key reason we’ve identified Ph.D. science student mentoring as an inspiration is because of its focus on project-based learning (e.g. the student thesis project) – an approach that makes it highly transferable to other disciplines/business sectors, particularly in high-tech / STEM focused sectors.

2. Benefits of a Mentoring Program for Your Business

Let’s take a moment to elaborate on the reasons you should consider establishing a mentoring program for your business.

As we touched on earlier, recruiting and retention are big concerns for many companies right now.

So is institutional knowledge (or domain expertise, or whatever term you happen to use) – when older workers that know how the job gets done walk out the door, they take with them vital information gleaned from years of on the job experience – so capturing that information and transferring it to a younger worker is vitally important. Related to this is the increasing amount of information necessary to perform work successfully – year after year, many jobs, particularly in high-tech STEM-oriented fields, require increasing amounts of specialized technical knowledge – making the need to transfer information to younger workers all the more imperative.

Another motivating factor for establishing a mentorship program in your company is to assist in diversity and inclusion programs.

For example, the field of manufacturing has historically faced challenges in hiring female STEM graduates, despite the fact that many high-tech manufacturing jobs are well paid and offer rewarding careers. Mentorships can help young women feel more connected to career opportunities they may not have considered before. And the same goes for young job candidates who may be “first in the family” to graduate from college or first in the family to have a professional job, and thus may need more guidance than those workers who come from a background where their family members were active in your particular line of work for generations.

Another important consideration in favor of establishing a mentoring program is that it aligns well with the current educational pedagogy that has guided the schooling of younger job candidates – many of whom were immersed in “flipped classrooms” where the teacher served as a facilitator (or mentor) for their education, and much of the education was based on “project-based learning” in small groups. For these younger workers, the idea of “rugged individualism” (e.g. working solo on job tasks) and a “sink or swim” management mentality of throwing younger workers into the deep end of the pool to get them launched into their careers seems unnecessarily cruel and out of touch with their educational background.

3. Overview of Mentoring Program Best Practices

What makes for an effective mentoring program?

Circumstances vary by company and by business sector, but here are some of the top considerations to keep in mind to make your program a success.

You Need to Walk before You Can Run

As with many new business initiatives, creating a pilot program is always a good idea. And when you can learn what works for your organization, then focus on scaling up to meet the needs of a greater number of employees.

One Size Does Not Fit All

Every business is different, so every mentorship program will be different. Likewise, not all seasoned employees are cut out to become good mentors – nor do all younger workers have the temperament and aspiration to participate in a mentorship program. That’s okay.

Keep it Low Key

Treat mentorship relationships inside the company with dignity and respect – oftentimes, this means maintaining privacy for individuals that are participating to avoid the unnecessary pressure or scrutiny on their performance that comes from singling them out. Save trumpeting the accomplishments and celebrating the achievements for major milestones only, such as when participants “graduate” from the program. (These milestones can also be promoted when you are actively recruiting new employees who will be very interested to learn about the benefits of your mentorship program.)

Mentoring Needs to Maintain Independence from the Manager/Boss

Quite a few managers these days identify with the role of a mentor to their direct reports already – which is great. However, in a formal mentorship program, you should try to pair up young workers with seasoned employees who do not manage them directly (where possible) to reduce the stress that comes with being honest about concerns over shortcomings and other insecurities. This is hard to do when facing your direct manager who also oversees your compensation and future career path.

Start with Shadowing Work, then Graduate to Independent Projects

Very junior employees receiving mentoring might not yet have been assigned independent projects that they are responsible for, so be cognizant of this. This is a good time to have younger workers shadow the work of the mentor to learn about company processes and career skills. As things progress, consider creating an independent project for the younger worker to accomplish on their own. This should be comfortable territory for younger employees who have been educated in the “project-based learning” curriculum common in today’s schools.

Train the Mentors to Be Effective Counselors

While mentoring may come naturally for many older employees, some will need some structured coaching on how to approach the role of being a mentor. Consider creating some hands-on classes that use role-play and perhaps video recordings of sample encounters to help improve mentoring skills for first-time mentors.

Voluntary, not Mandatory

Participating in a mentoring program should be an opt-in opportunity for both the mentors and those getting mentored. Making a program mandatory or part of the compensation matrix for receiving a raise or a bonus will put the wrong kind of emphasis on the program and undercut its effectiveness.

Combine Mentoring with Job Rotation

Historically, many companies have put promising young workers that have been identified as potential future executives through extensive job rotation so that they get broad experience throughout the company. Some firms, such as the energy giant, Shell, take this even further and require all their employees to rotate through different positions every four years or so. If you pursue this strategy, mentoring those who join new departments could significantly enhance its effectiveness.

Reverse Mentoring is a Thing

Don’t overlook the potential for younger workers to teach older workers new skills. For example, many younger workers are technologically adept with computers and software in ways that older employees might not be. Having a two-way mentorship can bring benefits across the board. For more information, see our article on reverse mentoring programs.

4. Learning to Become an Effective Mentor

Becoming an effective mentor is easier for those with experience in managing people or those who have a background in teaching – however, it’s not impossible for those who lack the skills to learn them.

That’s the view of Lucy Godley, who wrote a short article on Learning to Mentor published in Nature magazine when she was an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

Godley admits that transitioning from the role of being a student with a mentor to becoming a mentor herself was not as easy as she expected. She said she had to learn how to interact with people on a very personal level, which was new to her.

She recommends that mentors take the time to understand their protégés’ career aspirations first, then (in time) follow that up with a more difficult in-depth conversation about their individual strengths and weaknesses.

With this background, Godley works with each of her protégés to create a customized individual development plan (IDP) to identify short and long-term career goals as well as outline a step-by-step process to improve and build on their strengths as well as weaknesses.

There are other resources we can recommend that can help you become an effective mentor (even though some of these resources are focused on academia, they are equally useful in industry settings):

- Adviser, Teacher, Role Model, Friend– you On Being a Mentor to Students in Science and Engineering

- Entering Mentoring: A Seminar to Train a New Generation of Scientists

- How to Mentor Graduate Students: A Guide for Faculty at Diverse University

- RCR Mentoring: The Responsible Conduct of Research

5. Tips for How to Get the Most of a Mentor Relationship

When it comes to managing people, it’s important to always come back to the basic principle that:

We judge others by their actions.

We judge ourselves by our intentions.

If you’ve not heard this before, give it some thought, as it calls out a very common mismatch in expectations that can lead to serious misunderstandings and undermine the health of our relationships with our coworkers, if not also our families and friends.

Why do we bring this up when talking about how young employees should approach working with a mentor?

All too often, according to Hugh Kearns and Maria Gardiner, writing in Nature magazine, young people in a mentoring program can fall into the bad habit of establishing unrealistic expectations of what their mentor or advisor can do for them.

Kearns and Gardiner point out that sometimes the younger party assumes the role of a passive participant, operating under the false assumption that all the responsibility lies with the mentor to make things happen.

That’s generally not the case. So when reality crashes into plans and, for example, mentors get busy and have to reschedule meetings, the younger protégé should not wait passively for something to happen, they need to learn to follow up and keep at it (without becoming annoying, of course).

One way to keep on track is for the younger protégé to prepare a personal agenda for each meeting with their mentor by keeping a list of talking points handy based on what they need to talk about.

Kearns and Gardiner also make the point that the best mentoring relationships come about when each party treats it as a two-way street – the young protégé should be just as interested in their mentor’s interests and motivations as the other way around.

6. Creating a Mentoring Plan at Your Workplace

Establishing a mentoring program in the workplace can be a satisfying and worthwhile activity, especially if you set realistic expectations and content step-by-step.

As we touched on earlier, creating a pilot program first and learning from it is a good place to start.

That way, you can get a better idea of what works from practical experience as well as how to avoid potential pitfalls (some of which we have identified at the end of this article).

If someone in your organization has experience setting up a program such as SixSigma or some other management framework, talk to them. One piece of advice that is often emphasized is the need to establish a point person within the organization to oversee its success, rather than relying on multiple managers to make individual contributions and hope that the sum of the parts adds up to a whole.

As with every good project plan, it’s important to consider what kind of benchmarks you need to establish to measure success. We’ll touch on this more in the next section.

7. Funding a Mentoring Program and Calculating the Return on Investment

Justifying the expense of a mentorship program may require some creative accounting.

Don’t worry — we’re not suggesting something illegal or unethical. Instead, the potential benefits aren’t going to be all that straightforward to measure financially.

But here are some program justifications that you might want to consider:

Mentoring can build stronger relationships within an organization and thereby help retain both young workers as well as seasoned employees who can become attached to the program.

A mentoring program can also help your organization retain institutional knowledge by transferring important information from older workers who are near retirement to those younger workers who have many years of career ahead of them.

Bringing different groups of people together can often help spur spontaneous ideas, which can lead to greater success for the business.

Participants in a mentoring program can also experience increased job satisfaction, secure in the knowledge that what they share with other employees adds value and will provide long-standing contributions, even after they retire from the company.

Mentoring can also help strengthen diversity and inclusion programs, which is something we touched on at the beginning of this article. Hiring underprivileged workers or those with little familiarity with professional work is important, but it’s even more important to ensure that these hires get the training and experience they need to be successful over the long term.

Finally, if you are having difficulty justifying the cost of a mentoring program, consider the alternatives, which include sending employees off to get outside training, such as an online MBA program. Those programs are quite expensive and may not be as directly useful for your needs compared to what can be accomplished by a mentoring program that transfers the knowledge of your existing employees to younger workers.

8. Rolling out a Mentoring Program, including Recruiting Mentors and Mentees

What’s the best way to go about identifying potential mentors and younger workers to participate in a mentorship program?

For a smaller initial pilot program, it’s probably reasonable to select the candidates individually, then screen them to identify which ones have a positive outlook and interest to participate.

As we touched on earlier, it’s probably not a good idea to intertwine participation in a mentorship program with any other compensation program or career development activity.

Why?

It’s hoped this would help you attract candidates who want to participate because they’re interested in either helping others or helping themselves to improve – rather than seeking a checkmark to improve their chances for a bonus or raise or promotion.

On the other hand, some employees (either mentors or protégés) may view this as an extra (unpaid!) undue burden that would interfere with their regular work. Try to explain that mentoring will enhance their current work in a number of ways, but if you still get push back, then it’s probably time to move on and choose other candidates to participate.

9. Scaling Up a Mentoring Program to Serve a Wider Audience

Let’s say the initial mentoring pilot program has been a great success.

How do you scale it up to reach a larger audience?

The good news is that if people are having a positive experience, word will get around, and the next time you recruit participants, it will be easier.

Maintaining high standards will probably become an issue.

It may be time, for example, to create a slightly more formal training program to help orient those who are new to the program, particularly mentors who may not have much experience in working in a teaching/people role.

As your program expands, you may also want to consider whether you maintain a strict one-to-one relationship between one mentor and one protégé. Perhaps you could open it up to allow individual protégés to meet with more than one mentor. Likewise, you could also test whether mentors can effectively counsel small groups of protégés while continuing to meet for a one-on-one sessions for more personal growth discussions.

It’s also good to be aware that during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, many academic institutions had to quickly transition their mentoring programs to online platforms, such as Zoom or Skype. Given that many of us are working in hybrid workplaces, these tools can help bring people together who otherwise cannot meet face-to-face.

Academic institutions across the country have also experimented with dedicated mentoring platforms, and these are worth keeping tabs on as they may become suitable for use in industry settings. One such example is called MyNRMN — it’s a platform designed for collaborating in the fields of biomedical science. Another which was developed recently is Women in Science Without Borders (WISWB), which, as the name implies, focuses on mentoring and empowering young women in science.

10. Mentoring Program Pitfalls to Avoid

Finally, we like to point out a few pitfalls that you should try to avoid when establishing a mentoring program.

A Sink or Swim Approach Might Just Sink Your Mentoring Program

It bears repeating that thrusting unprepared mentors into the role without any background and training preparation could lead to major dissatisfaction among participants –possibly undermining the very success of your program before it gets off the ground.

Mentoring activities are Special – Not Just another Training Class

a mentoring program is not meant to be busy work, nor is it intended to be training classes under a different name. Mentors should not be reading PowerPoint presentations to the protégés, they should be having frank and candid conversations about personal aspirations and skills, ideally away from other coworkers in a private setting.

Why Not Just Send Young Students to Online Educational Programs?

We touched on this briefly in the discussion of how to justify the cost mentoring program.

In the old days, companies often sent promising him workers destined for senior management to get an MBA in a night school program. Today it’s much easier, with most programs offered online at your own pace.

So is an online program outside your company compared to an internal mentoring program?

The answer is there different, but they also might be complementary.

The benefit of an internal mentoring program is that big workers will get inside information from those with greater experience inside your company – helping to transfer knowledge between generations, for example.

In contrast, a nonaligned education program from an external institution might help provide an in-depth structured curriculum for learning important business or technical principles – though these are much less likely to be as specific to your line of work compared to getting information directly from experienced workers within your company.

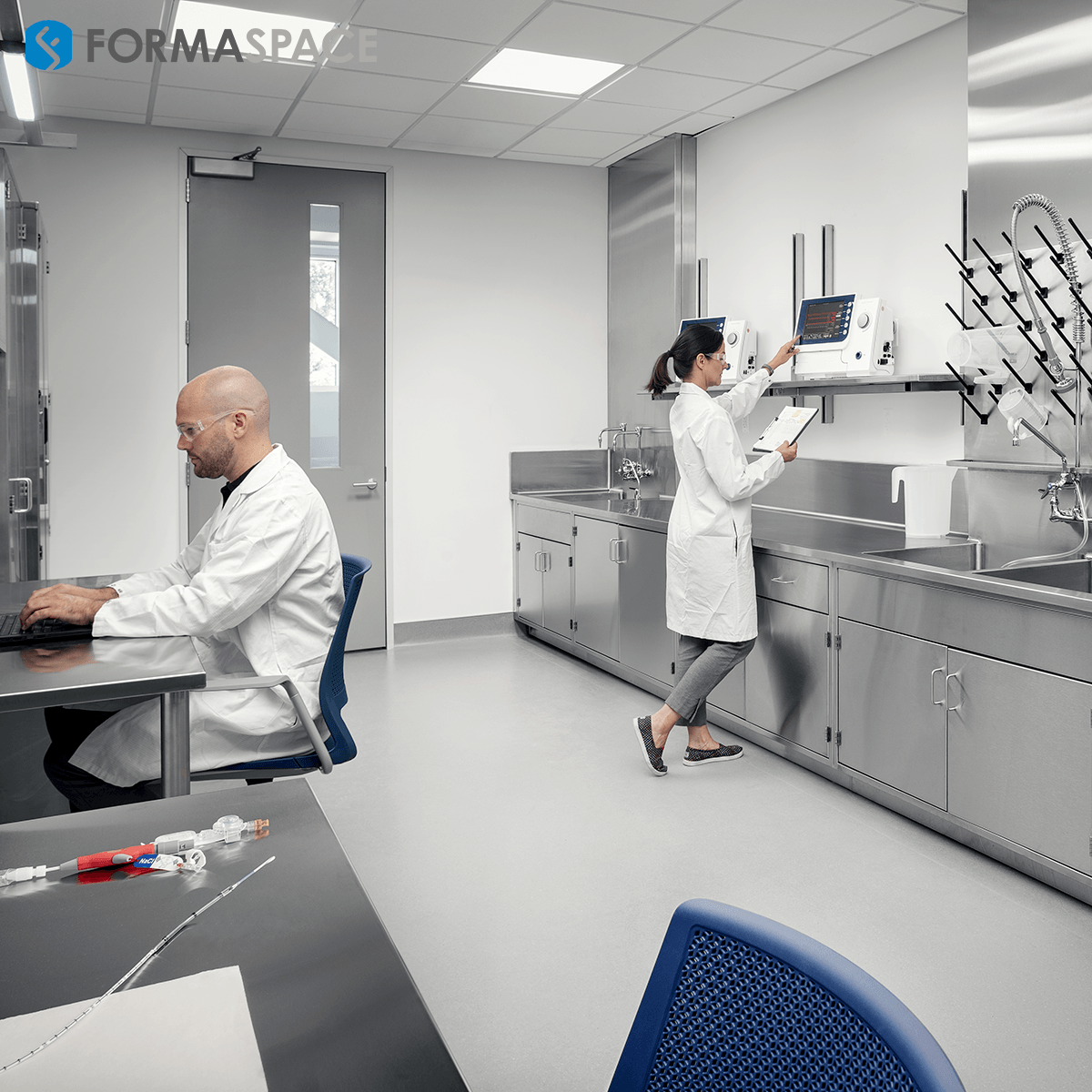

Formaspace is Your Partner for Inviting, Efficient, and Productive Workplaces

Whether you are working in an office, laboratory, research center, manufacturing plant, educational institution, or warehouse distribution center, Formaspace has custom solutions to make your business or institution more flexible, efficient, and productive.

If you can imagine it, we can build it at our factory headquarters in Austin, Texas.

Find out more today. Contact your Formaspace Design Consultant.